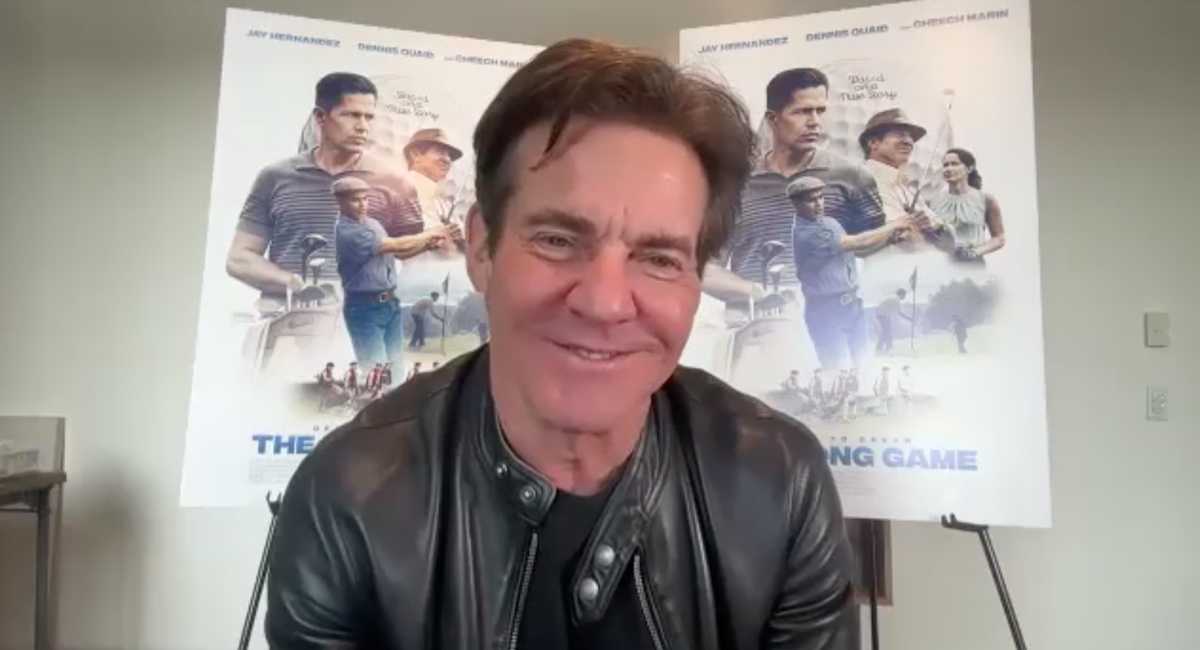

'Alita: Battle Angel' Director Robert Rodriguez on 'Taking a Vacation from Myself'

By his own admission, Robert Rodriguez’ “Alita: Battle Angel” is not the kind of adaptation that automatically has moviegoers worldwide thrilling at the news that their favorite character or comic book universe is finally coming to theaters. But adapted by James Cameron, who co-wrote the script (with "Avatar" confederate Laeta Kalogridis) and produced for Rodriguez, this film version of the popular manga by Yukito Kishiro offers the kind of world-building that only Cameron can create, brought to life using technology that few others can use more effectively. Meanwhile, this long-gestating story has only grown in relevance -- and resonance -- with its portrait of the title character, a young woman with a mysterious background who awakens in a strange world to discover that she has much more power than she yet realizes to take control and create change.

Moviefone recently caught up with Rodriguez, who was in Tokyo for a worldwide press tour, to discuss “Alita” and the challenge of shepherding another cinematic visionary’s ideas to the screen. In addition to talking about the artistic collaboration that came to fruition with Cameron after almost 25 years of friendship, Rodriguez reflected on the differences in working on a project where he could delegate some of the duties he often by necessity takes on himself, and revealed some of the lessons learned about his own process as a result of tackling a project whose ambitions and aims are radically different than his previous work. And finally, he offered some insights into what impact the Disney-Fox merger may have on additional installments in a larger narrative that this film’s vivid, detailed mythology sets up as a possibility.

Moviefone: When you started this process, what was this story about for you?

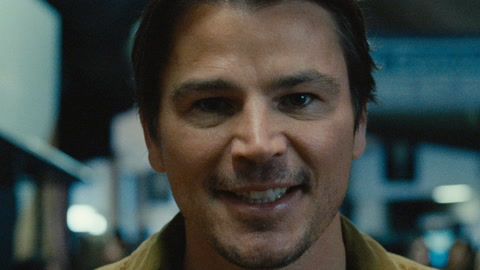

Robert Rodriguez: When I wrote Jim back after I read it, I said really identify with her -- this girl -- and I feel like if I identify with this 13-year-old girl, then you know it’s a very universal story that anyone could relate to. She grows up in a trash heap and thinks she’s insignificant, and finds she has great power, but then that’s not enough. You can teach young people to find their inner power and they'll find it pretty quickly, but it's like, what do you use that power for? She now has the benefit of this family life, which I loved the father-daughter relationship because I have a daughter that age. And I loved all the relationships; I could just identify with so much. It just felt like it would be a story that people could, through her eyes, find a story that really was relevant to them. And so I thought that's a great story. I’d love to get a story like that to tell the world. So it was definitely a response to the material. And the story seems very timely, but it was timely back in 1999 when he bought the rights. It was timely when he was going to make it in 2005. And in 2015 when we got it green lit, the studio said we need a movie like this! But you always need a movie like this. It's a very timeless story, and that's what I liked about it.

You’ve talked in the past about how you decided to edit James’ script almost as an exercise. But when time came to make the film did that mean you took more cues from his script than, say, the source material?

No one gets scripts like this. Guys like Jim are like Quentin -- they don't write scripts for anyone but themselves to direct. They would almost rather them sit in a drawer and rot than have somebody go make it wrong. So I knew it was a real gift that I was a friend of his and showed that I understood the material when I thoughtfully edited the script down without destroying what he loved about it. But it just read so fantastic. It wasn't like he had given me the books to adapt like I did on “Sin City.” He had already adapted it in such a brilliant way that it felt like a Jim Cameron movie -- the lost film that I always wanted to see.

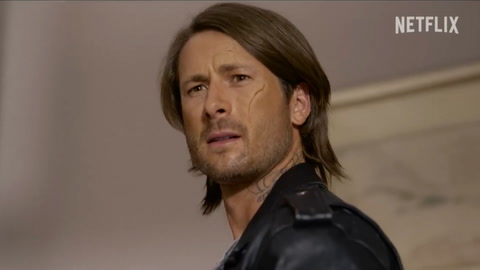

So instinctually I knew I couldn't just go do what I normally do, but I didn't have the analytics back then to figure out why or what that was until he and I talked. And I asked him, how do you approach this type of material, because your movies have such a signature to them. I want to try and ape that as much as possible just to do better to the material than going and doing it the Robert Rodriguez treatment. I mean that's what I didn't do on “Sin City” and on the stuff I do with Quentin -- I tried to do it in their style and keep it true to them. And he said, well, for me science fiction and fantasy has to be really grounded, truly believable, and utterly real. Otherwise you don't buy the fantasy. So I thought, I don't want to do green screen or have any layer of artifice over it -- no manga come to life stylizations. I want to go more grounded than even he’s done recently, so I'll try to build all sets, no green screen, locations that are real, real actors around her, just to really ground it and just have it be completely believable.

So across the board I had to do things differently than I normally do, but with great joy! I mean, it's always fun to take a vacation from yourself and try to learn how he crafts movies that appeal to a much bigger audience all around the world. I mean, that's really what I wanted it to be. Cause you could tell that's what it was when I read it.

James is tremendously detailed and dedicated about knowing how everything works technologically. Is that something you share? And how is that reflected in, say, something like the choice to make Alita’s eyes true to the manga?

Well, since she was a cyborg, you could get away with that, and that was kind of table stakes. Because when I saw the artwork he did in 2005 -- besides the script, he showed me the art reel that had tons of art production art that they do, pre-visualization and kind of photo real paintings that you could tell what it meant to convey. And the most arresting image that blew my mind was her looking at her porcelain-carved arms with these large manga eyes. And I thought, Oh crap, he was going for a full CG human back in 2005 but with the stylized eyes from the manga. He always does something new in his movies that you’ve just never seen before and I realized that that's what this was going to have. Then that was table stakes for the 2019 version -- it just had to have that. So that was just kind of a given, and if it made sense for him scientifically, then it made sense for me.

So when we talked about it, it was always that it was still going to be grounded. It was just going to give us something we knew we hadn't seen before. And then I like to go dive into the manga and pull extra things, because he'd really taken from Books One and Two mostly and Motorball from Book Three, and the rest of the books were pretty much untouched. I went and found some other things, but using that filter, the filter of Jim and does it feel real, does it not pull you out of the story, that just became my filter -- to keep it grounded, keep it real. Saving things for other stories, not trying to cram everything in.

When I did “Sin City,” I crammed all my favorite books into one movie because I didn't know if there'd be a sequel. I think if I adapted this myself, it would have been like trying to get the cake and eat it too. He had a much more disciplined approach to just building her as a character, giving her a great 180-degree arc so that by the end of the movie she knows exactly who she is and what she has to do. So I wanted to preserve all of that and not mess that up.

A lot of your effort seemed to be done in the editing phase to condense what I believe was a 300- or 400-page script. What was made easier for you when the filmmaking process actually began as a result of doing that and then what was maybe more difficult?

In hindsight it was so good to cut the script down so much ahead of time, because what I found, and this happened on “Avatar,” because there’s an effect in every shot, you really can’t judge the movie until it’s almost complete. You can't tell if scenes are even working if you’re constantly looking at her with a helmet on because you're not buying the character until it’s really done. And that's very expensive to do. If you're going to shoot scenes that ultimately you look at once they're done and go, yeah, that doesn't work, we should cut this down for time, that's why the pre-editing saved us a lot of money and time. Otherwise we would have been cutting sequences not in the edit room at their beginning because you couldn't judge it like that. You would have to wait until there was more done and that would be wasteful.

So I'm glad I cut it way down because ultimately, it's not Jim Cameron directing the movie, so Fox isn't going to give it that kind of a budget. I had to deliver a two-hour movie by contract, and I think it makes the movie much more of a rip-roaring tale because it has to run at that pace. I think the pace ends up being a lot tighter because of it. But that was really the reason - it was the first movie in a potential series but it's not a known character. So for all the economic reasons, I had to keep it tight and I think the story can always benefit from something like that.

How did delegating some of the responsibilities you typically take on yourself, doing cinematography, editing or score, make this a easier or more difficult process?

It was always out of necessity that I had to do all of those jobs. But as those movies went on, I had [directors of photography] like Guillermo Navarro, but then when I switched to digital, no d.p. wanted to touch that. So I went back to d.p.-ing. And I’ve used composers before but when I’d run out of money, I’d have to write the music myself, or I'd have to just edit because I knew the material better. But I've always enjoyed working with much better people, especially when I could afford them.

On this one, it was great; I mean, Jim knows how to do every job as well, but he chooses not to do that on his movie because there’s bigger fish to fry, and bigger movies. You still hire them, cast them -- like I don’t play every role in the movie, I cast the right actors so that role can be complete. So I cast the crew so that it could be something that I wouldn't be able to do myself. So [cinematographer] Bill Pope is amazing, [composer] Junkie XL, I loved his music for “Mad Max Fury Road,” and I can learn from these masters.

But also because I've done those jobs, communication with them is just so simple; they’re not used to having a director know their language and know their jobs so well so that we can just take it to a much bigger level faster. So I love doing that. If I have to save money on a movie, I probably would still do those jobs, but again, if I could afford a great master like that where that’s all they’re concentrated on, and it really does free you up to concentrate on what's most important -- the story and the characters. On this, people were shooting in 3D and you have to be watching that all the time, so you can only be so many places at once. I couldn't operate the camera as usual because it was a big 3D system on a crane that took three operators. It would be like, which guy am I going to be? I might as well not operate. So it would just distract me from what really was important.

James’ films reflect his style and his ideas as a storyteller. What are the things in “Alita” that reflect the story you know you’d tell if maybe you were doing it on your own, and what things because of Jim’s influence or his script would you naturally maybe not do as a storyteller or a director?

I was really glad he had taken a crack at the script first, because if I had just been handed all 30 of those books, I don’t think I would have been as excited. Because that’s a shitload of work -- I would have to read them all and try to figure out the story. But I liked how he saw the first two books as the key to the story, but also how he added more emotionality to it -- a lot more heart than was there. I tend to be a little more detached if I'm adapting something, kind of like, well, it is what it is - why not just make that? Because I like that. But I wouldn't take it as far as he did and to turn it into the kind of movie that he knew it needed to be in order to appeal to such a big audience.

He said to me early on, “I have to go for more emotion and more heart and a more of a cinematic story that can play around the world, because let's face it, this is a manga story. If we appeal just to manga fans for ‘Alita,’ we’re going to have a very small crowd. And we want to break new ground and have a lot more technology in this to do something people have never seen before. That's why I have to craft my stories.” I never had that approach to making movies.

When I made “Sin City,” I thought, I don't think anyone's even going to go to the theater. It's black and white. It's an anthology with voiceover and you’re not supposed to do any of those things. I just want to do it so badly that it's okay for me. I'll keep the budget low, and they will find it eventually on DVD, and I'm happy with that. And I was totally surprised they even went to the theater because I thought it's not going to look like anything else, and it didn't have “hit” written all over it at all. So I don't make those.

But that's not Jim. Jim goes and makes big hits because he wants to be able to pay for the technology that he's going to do to push it forward. So when I saw the script, that's all stuff that I would love to have gotten in a script. If somebody gave me a script to make that I didn't write myself, I would have done that movie. It’s just that somebody's got to come up with it. So I was glad that he had come up with it, because I loved how universal it was. I loved that it still had his quirky action, which was also Kishiro’s action. I mean that big bar fight, people say that's the part that we can tell is really you! And I say, that was actually in the comic and it was actually in Jim’s script. And then when I looked up the Top Ten Bar Fights just to see what people have done so I don't repeat it, I called Jim all excited and said, hey, four of the top bar fights are ours -- “Terminator,” “Terminator 2,” “Desperado” and “Dusk Till Dawn.” I guess this is just what we do -- we’ve got to top ourselves! So we like similar things, but I think his really go for the gold because his movies are just much, much bigger movies and that's just how he's been. I mean when he and I first met, he had made “Terminator 2,” the biggest movie of all time, and I had just done “El Mariachi.” That was the difference starting out the gate between me and him.

You talked about the expectation of success . But Disney taking over Fox seems to at least put a question mark on where a series like this could go in terms of who will pay for it and who is interested in it. How comfortable are you with this being a complete story, whether or not you directed what would be perhaps sequels to this, and how much expectation is there on moving forward with a bigger narrative?

We never thought, okay, we’re going to do Part One and we’re going to do three total. That’s never how Jim even thinks. That said, whenever he crafts the story he always thinks in terms of multiple movies just so he can write the main story. So in his outline, he’d go we don't really need to go to Zalem, you could save that for a second film -- and the third film would go to this level. It helps him craft a story, make it a complete story, so he knows when not to go trying to cram too much in there. That said, you can always go do sequels with all of the material between the books and stuff that he outlined. But it's really about, we’ve got to make the first movie work; we can’t have it not be a complete story. And I like those kinds of stories that leave you with a sense of what I call story value - like even if there was never a sequel, you can imagine more movies. Like she doesn't really know who she is until the last scene of the movie. But in “El Mariachi,” he didn’t get the guitar case full of guns, his signature weapon, until the last scene of the movie. In “Spy Kids,” they didn't actually become spies until the last scene in the movie. So even if you didn't make a sequel, you can imagine more because it's an origin story. So if Disney wants to do more, and this movie does well enough to warrant a sequel, we have places to go and we would all love to work on it. If it doesn't, it's a great one-off story that I think leaves you imagining more movies, which I still think are great stories to tell.

Alita: Battle Angel

When Alita awakens with no memory of who she is in a future world she does not recognize, she is taken in by Ido, a compassionate doctor who realizes that somewhere... Read the Plot