Jon Stewart and Brian Williams: TV News, Entertainment, and Accountability

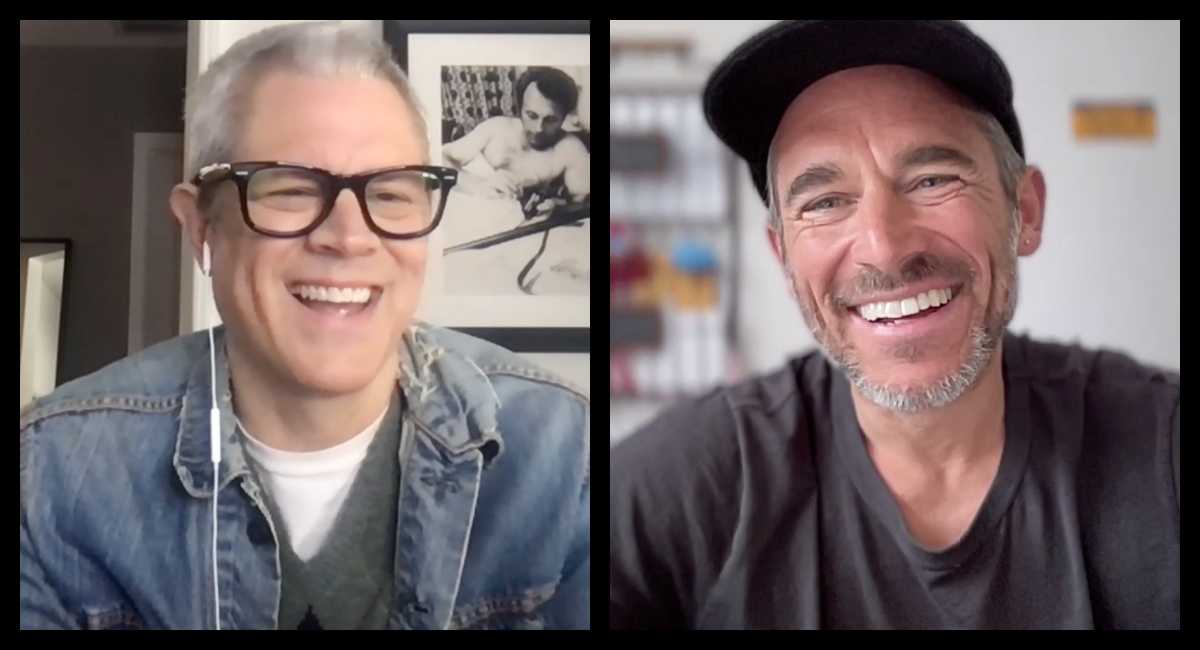

There has been a lot of chatter -- jokes, tweets, rueful speculation -- noting the paradox of Brian Williams' forced six-month leave from the anchor chair at "NBC Nightly News" and Jon Stewart's near-simultaneous announcement of his retirement from "The Daily Show," but the biggest irony may be this one: we all care who'll replace Stewart (if, indeed, anyone can) but aren't the least bit concerned with who's replacing Williams (Lester Holt, as it turns out). And the reason is simple: we consider fake newsman Stewart accountable, while we hold no such expectations for real newsman Williams.

The truth is, Stewart and Williams -- who seem like pals whenever the latter visits the former's show -- have a lot more in common than either would probably like to admit. They're both from Jersey, both telegenic, both funny. Indeed, it's Williams' efforts to be amusing that seem to have led to his undoing. It's one thing that he's the loosest of all network nightly news anchors -- cracking wise with Stewart and David Letterman, rapping the news with Jimmy Fallon, performing in self-mocking cameos on "30 Rock" and as the guest host of "Saturday Night Live" -- but his apparent desire to be a raconteur and not just a news reader seems to have led to his alleged falsehoods, his supposed embellishing his tales from the field in Iraq and New Orleans with self-aggrandizing details that made his personal anecdotes (if not his actual reporting) more dramatic.

As Stewart himself noted the other night, it seems unfair that Williams is the only person who's ever been punished for the lies surrounding the Iraq War. For one thing, it's curious that, for more than a decade, Williams got away with telling his story about being shot down in a helicopter when there were military witnesses who could debunk it. Why didn't we hear from them sooner? It was to someone's benefit -- not just Williams' -- to keep the truth silent. Williams' story didn't just help sell his own image as an intrepid field reporter, it helped sell the Iraq War. It became part of the official narrative of the war, one that went unquestioned, not just at NBC News, but at all the TV news operations.

One of the few outlets that did question the official narrative of the war was, of course, "The Daily Show." It's worth remembering that the Comedy Central show's project, under Stewart, has not just been to poke fun at lying politicians, but to skewer even more mercilessly the news media that repeat those lies without bothering to check them out. Some media critics complain of newscasters' liberal bias or conservative bias, but as "The Daily Show" has pointed out over and over, TV news is biased toward laziness and sloppiness. Checking facts and debunking lies is difficult and costly, and besides, it's hard to get viewers to pay attention to the truth if it's less dramatic than a lie, or if it doesn't fit the established narrative. All that has been the conventional wisdom behind TV news, even though Stewart and his team of writers and researchers have proved over and over that, with enough diligence and skepticism, it actually is possible to debunk falsehoods on a budget, to tell truths that don't fit the established narrative, and to do so in an entertaining way -- in other words, to produce real journalism that people will actually watch and trust.

In fact, one reason Stewart says he's leaving is that he doesn't want to become mediocre and complacent -- as he put it, viewers deserve better than a restless host. And Stewart's restlessness has become impossible to ignore over the past five years. His "Rally to Restore Sanity" in Washington in 2010 may have been aa big stunt, but it seemed to stem from Stewart's oft-stated complaint that civil discourse in America has become impossibly poisoned by partisan rancor, fueled in part by cable TV journalists shouting at each other. (Before that, he famously criticized the panelists on "Crossfire" for hurting America with their more-heat-than-light arguments, criticism that actually shamed CNN into canceling the show for a few years.) In 2013, he took a summer leave to write and direct his first film, "Rosewater," inspired by the story of Iranian journalist Maziar Bahari, punished by the regime at home in part for his appearance on "The Daily Show." In other words, Stewart actually felt accountable for an injustice that occurred in part because of something he aired, then found a platform where he could report a story that brought wider attention to that injustice. It's that kind of accountability, not to mention enterprise, that we used to expect from real journalists.

By the way, Bahari was imprisoned in Iran because the regime considered him a spy or at least a stooge of the American government. In the U.S., and especially at NBC, being though a government stooge or a useful idiot seems to be a badge of honor. During the Scooter Libby trial in 2007, VIce President Dick Cheney's former communications director Cathie Martin testified that Cheney liked to appear on NBC's "Meet the Press" because he could spin his message however he pleased without being confronted by tough questions. During the same trial, then-host Tim Russert testified that he considered all phone calls with senior government officials to be off-the-record unless he later asked their permission to reveal their remarks -- the exact opposite of standard journalistic practice. But then, Russert didn't want to alienate his sources and lose access to them. And maintaining access to top politicians, not holding them accountable or enlightening viewers, is what the Sunday morning shows like "Meet the Press" are all about.

And Russert wasn't alone; the rest of the Washington media that revered Russert behaved the same way. Stewart protege Stephen Colbert pointed this out in his infamous White House Correspondents Dinner speech in 2006. ("Here's how it works. The president makes decisions. He's the decider. The press secretary announces those decisions, and you people of the press type those decisions down. Make, announce, type. Just put 'em through a spell check and go home.") Colbert fans rate this as one of the comic's funniest moments, but the Washington media were not amused and griped that Colbert had cast a pall over their banquet.

Nonetheless, last fall, as NBC News was struggling to find a host for "Meet the Press" who could reverse the show's ratings slide under Russert successor David Gregory, the network floated the idea of hiring Stewart. That idea sounded absurd to many, including Stewart himself, but it was actually a backhanded compliment, an acknowledgement that Stewart had succeeded where Gregory had failed, in producing a newscast that contained actual nuggets of journalism and was, more important, entertaining enough to draw and hold viewers.

That, after all, is the mission of TV news operations these days. Viewers with long memories may recall that TV news was once considered a public trust, a duty, the civic service that networks and local stations performed in order to maintain their broadcast licenses. The advent of cable news proved, however, that newscasting could be not just an obligation but a revenue generator. As a result, TV news became more lurid and dramatic and less informative. It also became more celebrity-obsessed, whether the celebrities were news subjects, interview guests, or the network's own correspondents.

In an atmosphere like that, it's no wonder that NBC pursued Stewart, or that Williams tried to make himself more entertaining. It's a bitter irony that the network is punishing him for doing what Gregory failed to do and what it would have hired Stewart to do.

A final thought: the phrase "end of an era" has been tossed around a lot this week, but the real end of an era may be the one marked by the death of "^60 Minutes" correspondent Bob Simon in a Manhattan car crash on Wednesday. Simon, who'd been with CBS for nearly half a century, had reported from war zones and other trouble spots from Vietnam to present-day Iraq. Sure, he was as capable of reporting on Hollywood as on Hezbollah, but he still managed to win 27 Emmys for a career spent bringing back stories from dangerous places. In 1992, during the Gulf War, he and his crew were thrown in an Iraqi prison and beaten frequently during 40 days of captivity. He wrote a book about the experience but felt some guilt about touting his own story when others had faced far worse. He never became a news anchor (that is, a glorified reader of reporting done by others) but was still hard at work as part of the "60 Minutes" team at age 73. A career like his -- routinely placing his life in jeopardy to report from places Americans can't find on a map -- is unimaginable for anyone starting out in TV news today. But you don't get to tell those kinds of stories if you're stuck behind a desk. No wonder Williams tried to get out every once in a while and generate those stories himself, and no wonder Stewart wants to get out and do the same.