How Jonathan Nolan & Lisa Joy Built a Bleaker, Badder 'Westworld'

Is Westworld an amusement park, or an abusement park?

That's the question at the center of HBO's sumptuous new sci-fi series, based on the increasingly prophetic 1973 movie written and directed by novelist Michael Crichton, in which he first explored the topic of a cutting-edge public playground where the amusements -- this time in the form of cowboys rather than "Jurassic Park's" dinosaurs -- wreck havoc.

In the new "Westworld," however, the human guests may pose far more danger to the AI hosts, acting out on some of their cruelest, most debasing impulses against the mechanized inhabitants of a realistically recreated Old West environment. But what happens if the artificial entertainments suddenly become knowingly and painfully aware of their treatment, both good and horrible?

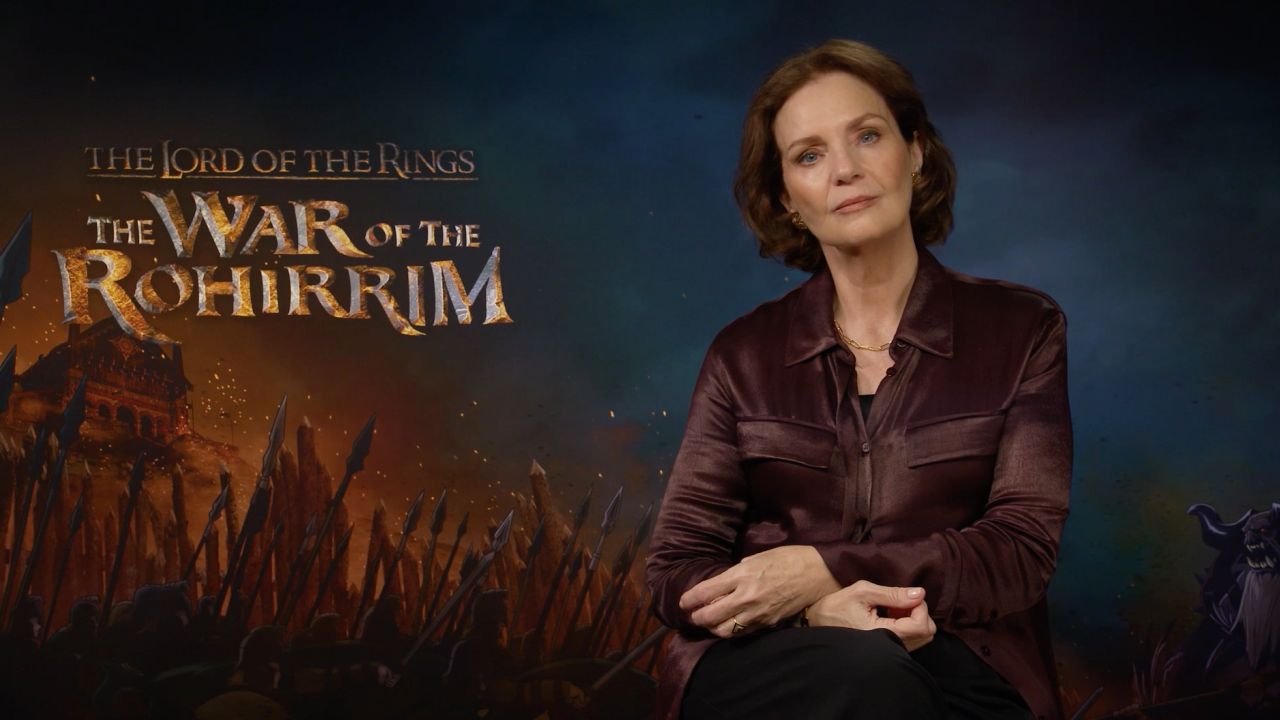

Screenwriters Person of Interest") and Pushing Daisies," "Burn Notice"), who also happen to be husband and wife, have teamed with executive producer J.J. Abrams and an all-star cast -- one that includes Anthony Hopkins, Evan Rachel Wood, Ed Harris, Thandie Newton, and James Marsden -- on the project, bringing a disquieting and increasingly existential twist to the original setup, as they revealed to Moviefone. "The original film is about humans trapped in a theme park with robots running amok," says Nolan. "Our show is about robots trapped in a theme park with humans running amok."

Moviefone: When you both sat down with this project in mind and looked at Crichton's work, tell me what started popping in your brain as to the things you wanted to figure out what to do with and the way you wanted to go in different directions.

Lisa Joy: When I first agreed to do the project, to be totally honest, I hadn't seen the movie yet. And I didn't know if I should see it at that point, because we'd already started talking to J.J., and just the concept of, it's a theme park with robots where you can go and do whatever you want -- I thought, "My God, that's genius!"

And it is genius. Crichton is genius. The possibilities of new types of characters that I hadn't seen before in Western or sci-fi started fumbling around in my head and in our conversations. I was just really excited to explore that. Now, Jonah had seen the movie.

Jonathan Nolan: I'd seen the film as a kid, yeah. It scared the crap out of me. I still have issues with Yul Brynner. The original film is so cool. Crichton directed it -- wrote and directed it when he was 30 years old -- it was his directorial debut, and it's so packed with ideas. Even watching them again, it's so hard to understand how much he was thinking about the future.

One good example is, at one point, there was a passing reference in there, when the chief scientist of the park is trying to figure out what's going wrong with the robots. There's glancing reference to, it's spreading between them like a virus. You can kind of roll your eyes, and you're like, "Right, a computer virus." I went back and looked into it: he wrote it in '72/'73, and the first computer virus didn't appear until '74. So here's a guy who's anticipating -- and that's a pretty big idea, the idea of a virus might be applicable to digital creation.

So the original film is packed full of ideas. It's breathless. And that was Crichton all over: so brilliant and so many ideas, and he barely had a chance to explore them. I've worked in film and TV. Film is good for some projects. What was so attractive for us about this as an episodic piece of storytelling was the ability to really dig deep into that question of consciousness, of artificial consciousness.

That key insight about starting with the host's perspective and kind of coming into it with the guests, I think, really unlocked the experience for us. I love stories and storytelling that involves some limitation on the protagonist's understanding of the world, and this is a really fun one. They're not allowed to remember the things that happen to them. They're not allowed to see the cracks in their world. The joke is on them. And watching them not only come to consciousness, but also come to the realization of where they really are and what they're really designed to do, is a really cool journey.

The idea that our technological offspring might pose some problems for us has been around in different forms, from "Frankenstein" to "Blade Runner." In this day and age, what were the issues that really caught your attention that you wanted to explore, to express in a literal or allegorical way?

Joy: We often talk about the show as an examination of human nature. I think one facet of that is these AI are creatures of our creation. We are their mothers and fathers. That's a way of looking at it. So you start thinking about what their characterizations mean as merit to us. If they do bad, if they do good, if they are innocent, that's part of what we fed them. That's part of what we put into them. So in that way, it's a mirror into our own psyches.

I think now, as we're developing these actual technologies, the thing is, just like with an actual child, you hopefully -- I think, if you're a good parent -- want your children to be better than you, in every way. More moral, more happy, more kind, more giving. At least that's how I believe. But they don't get that if you don't code that. And you won't code that if you yourself don't feel that. So it's about inputs and responsibility of what inputs we feed these synthetic children.

Is there an aspect of that equation for you, Jonah, that also kind of kept itching at the back of your brain?

Nolan: Yeah, very much. For me, we've seen an awful lot of film and television that considers this question from the sort of pejorative or dystopian perspective. The AI is going to kill us or enslave us. I, for a long time, have been more interested in looking at it from the other perspective of, "What will they think of us? What will they make of us?" In the same way that when you have a child, you begin to wonder what they think of you.

You begin to think about what you do, and the work that you do, and how you behave, and how you hold yourself, how you comport yourself from your child's perspective. You find yourself getting upset or using bad language. You change. So I'm fascinated by this proposition of what they will learn from us, take from us, and whether they will want to be human.

And everyone involved in this project and everyone watching this project has the same limitation, which we are all human beings. And [Anthony Hopkin's] character, Ford, talks about this in a later episode: we only have human consciousness, it's the only yardstick we know for consciousness. But it is clearly very flawed. Look at the world around you. We're far from perfect. So these creatures looking at us and wondering, do we have to be like them? They made us like them, do we have to remain that way? It's one of the questions we wanted to ask.

With a project like this, with hopefully a long future ahead of it, a lot of the heavy lifting has to be done creating the mythology. Tell me about the fun of that, the challenge of that, and maybe where your friend J.J. Abrams, who knows his way around that came in and sprinkled his little spices along the way.

Nolan: You know, we joke about the obvious analogy to "Game of Thrones" -- very different shows, but we looked at "Game of Thrones" as a model for, how do you do a big-scope television show -- in a lot of ways, in terms of the scope and ambition of the storytelling, but also the production value?

Obviously, we have the original film, which has so many brilliant ideas in it, but we don't have the novels. We don't have George R. R. Martin and the books. So our joke has been that part of the season in writing this thing was, "First we write the novels, then we adapt them internally." That's been daunting, but a lot of fun. A great deal of fun. There are so many places this story can go.

Joy: There's so many. I remember when we were first breaking it, Jonah and I, we just had our first child. Actually, we started breaking it even before when I was still pregnant. We would work in my office at home, and we had all these pages and pages that we would write on and scribble on, and then stick to the wall. And by the time it was done, all four walls were just totally covered in pages with like arrows to here and interconnecting different things and different characters we were exploring, and backstories.

We wanted to really have an understanding of which characters -- it was at that point that all the characters were coming alive for us, and we were exploring all that. We got through some of that in the first season, but we actually thought far beyond that into the next few seasons. With the kind of middle point and even an end point to it. So we did a lot of initial thinking about the mythology, and it helped us, I think, even if we haven't gotten to some of that yet. It helped informed how we write what we're writing now.

There's something analogous to your jobs as writers as to what some of your characters are doing in this show. You sometimes have to torture a character for drama. Sometimes you fall in love with characters you write and you don't want to do these things to them. Can you talk a little bit about that element of transference from your life to this fantasy world?

Nolan: Yeah, there was a great moment when a couple of our actors were rehearsing a scene. They said, "We finally figured out what this is like." They were like, "This is us. This is what we do. This is you. You're the writers, and you tell us what to do."

I'm not typically drawn to workplace dramas, and I don't think what we do is terribly interesting, which is why we tend to write about things that are in genre, in terms of the writing and producing and the directing. But there is a little bit of a crossover here, and more than a little bit of an analogy between the creative work that's going on down below, and the narratives that are being lived out up above.

I hasten to point out that Simon Quarterman's character, Lee Sizemore, the writer, bears absolutely no resemblance to any writers that we may know or worked with over the years, whatsoever!

"Westworld" premieres Sunday, October 3rd, on HBO.