'Missing Link' Director Chris Butler on His Adventures Through Stop-Motion

Although you might not know his name, Chris Butler is one of the most exciting and important voices in modern animation and his latest film as a writer/director, this weekend’s “Missing Link,” might be his best. Butler started working in animation on direct-to-video sequels for Disney, before segueing to the fascinating world of stop-motion animation, where he has flourished as a storyboard artist, designer, writer and director (he has worked, in various capacities, on every Laika film besides “The Boxtrolls,” including Laika founder Travis Knight's awe-inspiring "Kubo and the Two Strings").

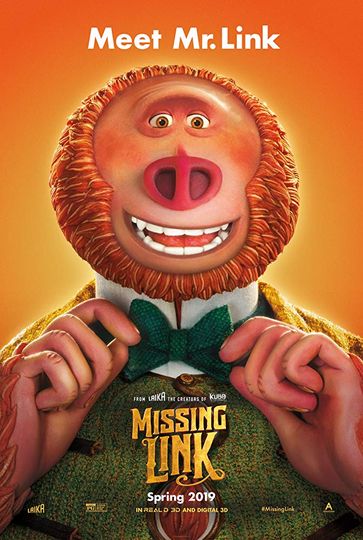

“Missing Link,” his latest film as a writer and director for the Portland, Oregon-based Laika, tells the story of Sir Lionel Frost (Hugh Jackman), an arrogant adventurer whose latest quest involves returning Bigfoot aka Mr. Link (Zach Galifianakis) to Shangri-La, so that he can reconnect with his fellow Yetis (the Yeti queen is voiced by Emma Thompson). It’s a wonderful, globe-trotting adventure and absolutely stunning to behold, bigger and brighter and more joyful than anything Laika has done yet.

So you can imagine how thrilled we were to get to chat with Butler about his journey in animation, what makes this form of animation so essential to him, where the story for “Missing Link” came from and what is coming next.

Moviefone: How did you end up in stop-motion animation? Was it something you always wanted to do?

Chris Butler: I started out wanting to be a 2D animator. I am really old, so I grew up in a time when 2D animation was pretty much all you got. There was certainly no CG. So I always wanted to do drawn animation. I was obsessed with Disney back then. This was at a time when the animation industry was not at its best. There wasn't a huge amount of stuff going on, certainly not in England. There was a lot of commercial work but certainly no feature work. I think animation has enjoyed such a vibrant renaissance over the last 15 years and that was not the case back then. So you took what was you could get. I remember hearing that Tim Burton and was going to make another stop-motion movie in London, “The Corpse Bride.”

I was storyboarding back then and I thought, I am going to work on this. I had dabbled in stop-motion on and off but not in this way. I always talk about how inspirational it was to me as a filmmaker because when you're storyboarding or trying to think of a shot or how you're cutting from one thing to another, you just trying to think dynamically about how to frame that part of the scene. But really it's just in your head. With this I got to walk down onto the set and I could be in the place that the story is happening. And I could imagine, Well, if I put the camera here, if I put the camera here, if I move the puppet here and it started to make me really think about filmmaking in a way that I hadn't done before.

As a story artist I was really just thinking about gags and funny drawings but this made me think about cutting and continuity and framing and composition, way more than I had done before. I was sold after that.

I loved that experience and I just wanted to work more and more in stop-motion. And I got the opportunity to work on “Coraline.” I'd heard that “Caroline” was going to start up at Laika in Portland. I didn't know much more than that. But I wanted to work with Henry Selick and this was an opportunity. So I came out to Portland. I didn't even come out for an interview or to check the place out. I just packed my bag and left. I think I agreed to come for six months and that was 13 years ago. It was so something worked out.

Well you act as creative continuity through almost all of the features. What is it about Laika and that process that makes you just kind of like go into it so wholeheartedly, no matter the project?

My situation at Laika is unique. I never expected for that to happen. You seldom get the opportunity as an artist to do what you want and as a storyteller to tell exactly the story that you want to tell and not have a million different hands grab onto it and try to make it into something else. I got that opportunity at Laika. I showed parts of the script to “ParaNorman” to Travis and he said, “I want to make this movie and I want you to direct it.” Of course I did it with Sam Fell, but at no point did it feel like it needed to evolve into something else. It was like, I love this and we're going to make this and that's just unheard of. No one these days gets that opportunity. And I've had it twice!

After “ParaNorman” finished, I did work on “Kubo,” but Travis said to me, “What do you want to do next?” And I had this grab bag of ideas that I've worked on, on and off for a long time and I pulled one out, dusted it down and said, “What do you think about this?” And that became “Missing Link.” So I am spoiled when it comes to creativity and I think that's why I'm there. There is a refreshing perspective at the studio, which is that the creator really is the creator -- it can be one person's vision and that can become a great animated movie.

So how fully formed was “Missing Link” because it seems like the production, at least publicly, was pretty quick, right?

No. I think it's our longest production. It was five years total. The development was very brief and I think that's because the story was already quite well formed. It was in development for about a year. That's when I was working on the script and starting initial concept work. Pre-production, when you really get into the design and the building of the assets, that was about a year as well. So was also very quick. The shooting itself was two years. And that's pretty long because it was such an ambitious project. It was the most number of sets we've ever had, with an incredible amount of location changes and background characters. So it was a hugely complex undertaking. The story itself, I pretty much knew what it was. So it didn't go through a lot of rewrites, really. Maybe two, three drafts total. I think that’s because I'd been working on it for a long time before I showed it to Travis. And I think the other thing is if you're the writer and the director, it's kind of easier in a way because you're writing exactly what you want to see on the screen.

Well, I was going to ask, what was the sort of initial hook for you? Was it doing a movie about the Yeti and bigfoot?

My favorite movie of all time is “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” And I thought, Wouldn't it be great if I could a stop-motion Indiana Jones-kind of story? So that would be initial hook. Interestingly enough, I came up with the character of Sir Lionel Frost, and I thought of him as a combination of Sherlock Holmes and Indiana Jones. Obviously the time periods, and the eccentricity, the borderline sociopathy are, that's more Sherlock Holmes but the action adventure hero, that's Indy.

But the original story that I came up with, there was no Mr. Link, it was a different kind of creature. I came up with this story and I was really happy with the story. But and at the same time, other ideas were sparking. So I wrote another adventure for the same character and this was the one with Mr. Link. It became clear very, very quickly that the greatest hook for any of this adventure was back character. He immediately became the heart of it. So I discarded that first story and concentrated on the, on the second one in practice and it became very much a story about Mr. Link rather than the adventurer.

Could you talk about the look of the movie? You have a furry character but you decided to not go with the Rankin/Bass look with the “boiling” fur. Can you talk about that decision?

It was a couple of things actually. I'm by no means a stop-motion purist. I love all the different looks that you can achieve with stop-motion. So I love when Wes Anderson makes a stop-motion movie. But that’s not what I wanted to do. I wanted to have my own look and I wanted to take full advantage of all the innovations that we've been exploring for the last four movies. And I also wanted to stylize it in a way that was pretty aggressive. I wanted this movie to be big, bold, colorful and playful and part of that was this graphic stylization, this angularity. That came from these initial character designs that I did. I think because the look of it was so stylized, it became clear very quickly that the hair on the characters would need to be similarly stylized.

I wanted Link’s fur to look like it was the same material that's on the top of the characters’ head. So having a real fur would have just looked like it was a different movie. And in a way, it allowed us to explore his construction in a way that was unique. He is a unique creation. He’s incredibly challenging as a puppet build because of all that hair. And the way we approached it in the end was almost like scales. So these little tufts can ride over the top of each other and you can achieve a lot of elasticity without having all the silicon bunch up. So it was challenging. But I think what we got exists in this world incredibly well. He fits. And he looks pretty cool as well.

You talk about innovation and, and it seemed like there was a bunch of CGI in this movie. Were those CGI fixes helpful in wrestling this thing to the ground?

I don't think we would've been able to make it without CGI extras. Because you could never animate that many puppets in a crowd. So yes, an awful lot of CG. And that's the thing. If you’re making a travelogue, if you’re making “Around the world in 80 Days” and you're going to 10 different countries, those countries have to be populated. Otherwise it's a different kind of movie. So I knew that was going to be a challenge. I think the VFX group had done astonishing things with our CG characters over the years and I was so impressed with what they did here because it's a pet peeve of mine when you see an animated movie where the background characters look different from the foreground characters, they lot of less thought out or more identical. And I didn't want that.

So we came up with a pretty complex system that allowed us to visit these very different places and have very different looks, very different costumes, very different facial hair everywhere we went. And it's pretty hard to pick out a repeat in all these scenes. I was thrilled with what we came up with.

There's a lot of puppets as well though. I certainly don't want to take away from the puppet department because they had their work more than cut out. I think you also have to be very careful about how you shoot these things. I had a scene in New York docks and I didn't want us to have to build an entirety of New York docks, because it was for a handful of shots. So we were very careful about how we compose those shots that immediately say you are about to embark on a sea journey. But you're doing it in a very thoughtful, montage-like way that checks all the boxes but makes you think you're in a much bigger place.

So what’s next? Are you, like Travis, being seduced by live-action?

I haven't really thought about it to be honest. My head is still very much in this movie because we only finished it a couple of weeks ago. So all I can think about right now is a vacation would be nice. I would actually like to do some writing. I think that's probably one of my favorite parts of the process. We have a crew of 450 people so you're around a lot of people a lot of the time. The writing part means I can go and disappear in a hotel room somewhere and just disappear into a fantasy world. So … some writing next. But vacation first.

"Missing Link" opens everywhere on Friday.