Oscars 2018: Why Your Favorite Movie Has a Good Shot at Winning This Year

It's still way too early to predict who'll win at the Oscars, which are still two long months away. But we can predict the shape and character of the Oscar race. And we can tell you this: it's gonna be ugly.

Remember the complaints in recent years over inclusiveness and diversity among the nominees, neatly summed up by the hashtag campaign #OscarsSoWhite? Remember how lest year's Oscar race ended with the absurd and colossal screw-up of "La La Land" being announced Best Picture winner in front of a billion people, only to have to give up the trophy a minute later to actual winner "Moonlight"?

Well, those controversies are going to seem like goofy, harmless Will Ferrell comedies compared to how this year's race is likely to shake out.

The reason? Well, think of the Oscars as more than just a list of the year's best movies and performances. As a group, each year's Academy Awards represents something more: the way Hollywood wants to present itself to the world, the industry's best possible face.

And for about a quarter century, that face has been Harvey Weinstein's.

For decades now, Weinstein has dominated the Oscars, both as the producer of countless trophy-grabbing movies, and as the most skilled campaigner in any year's Oscar race. As the head honcho of Miramax and later the Weinstein Company, he orchestrated a power shift at the Academy Awards from the major Hollywood studios to the independent distributors, a shift represented by the notorious 1999 upset victory of his "Shakespeare in Love" over "Saving Private Ryan." More than that, he crafted the blueprint for the kind of movies that win Oscars --often classy, historical, and British.

The shift in the Academy's taste that Weinstein orchestrated may have been self-serving, but he did the industry a favor. Weinstein's wins allowed Hollywood to present itself, for at least a few weeks each year, as a serious place that made thoughtful, literate, grown-up films that took important stands on social and political issues.

Now, however, Weinstein's is the face of Hollywood's avalanche of disgraced sexual predators. The revelations of systemic sexual harassment throughout the industry that began with Weinstein's fall from grace three months ago seem to implicate a new Hollywood power player almost every day. Which is why it'll be hard to watch all the Oscar campaigning this year -- whether it's serious talk about the merits of the competing movies or the gossipy discussion on the season's red carpets -- and not notice the dark shadow that the ongoing grotesqueness of the scandal casts over the glossy pageantry or the movies themselves. How is the industry supposed to honor its best and present itself as a place that rewards merit and achievement at a time when its dirtiest laundry is airing in public?

Sure, the awards voters and movie stars are going to try to acknowledge the elephant in the room. At the Golden Globes this Sunday, actresses will make a statement against sexism by forgoing colorful gowns and dressing in black. At the Screen Actors Guild Awards on Jan. 21 (days before the Oscar nominations are announced), all the presenters will be women. No doubt there will be critics who argue that such superficial gestures do little to make up for decades of industry-enabled harassment or to prevent similar misdeeds in the future. Still, it's better than behaving like it's business as usual and pretending that the industry is not in a state of upheaval.

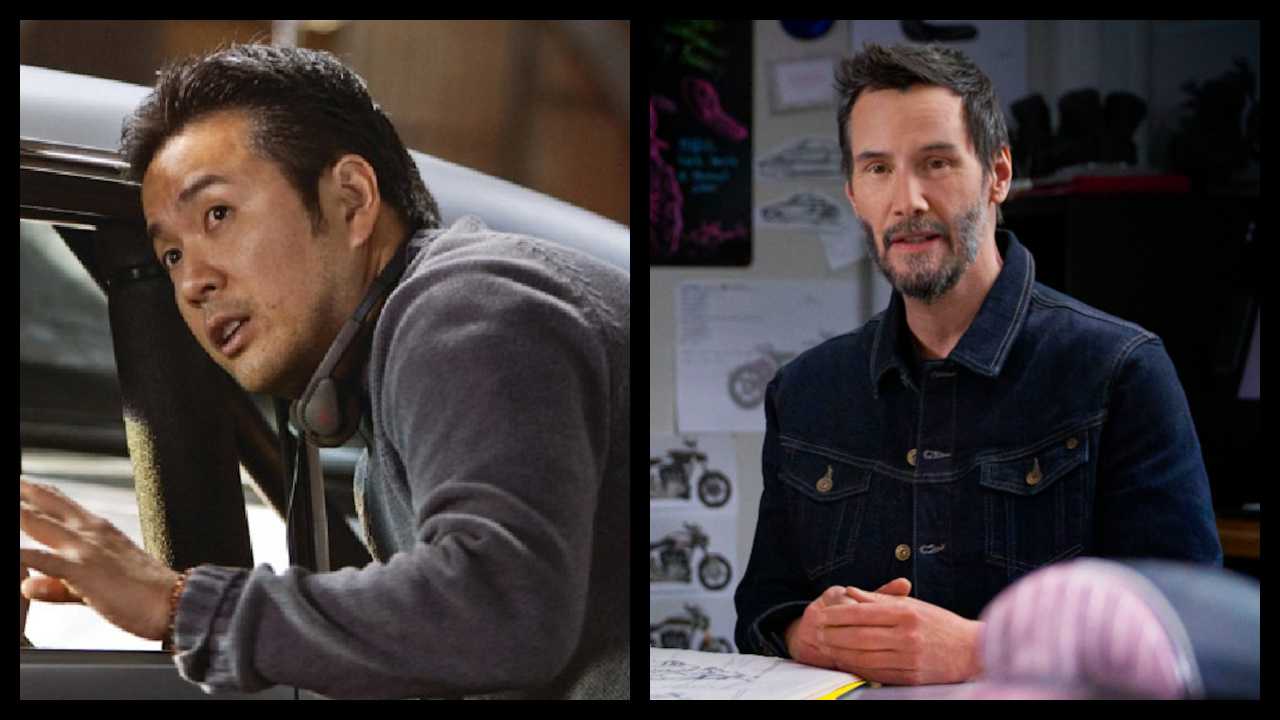

But it's also true that none of these protest gestures will address the imbalances that have led to the current slate of awards contenders. Despite the strides made last year, with the victory of "Moonlight" and the nominations and awards for a diverse array of artists after the long #OscarsSoWhite drought, Hollywood's inclusiveness problems are far from solved. Already this season, awards tastemakers have been accused of giving short shrift to filmmakers like Dee Rees (the African-American woman who directed the acclaimed, Netflix-backed drama "Mudbound"), Kumail Nanjiani (co-writer and star of this summer's indie hit "The Big Sick"), and Greta Gerwig (writer/director of the universally adored "Lady Bird").

Jordan Peele may be overlooked for "Get Out," one of 2017's biggest hits and best-reviewed movies, though that may have more to do with Academy bias against horror than against biracial writer/directors. Same goes for superhero spectacle "Wonder Woman," which, despite being a huge hit with a topical social conscience, will probably not get much Oscar love, more because of its genre than because a woman (Patty Jenkins) directed it.

The Best Picture race is shaping up to be a contest between traditional historical epics -- namely, "Dunkirk," "Darkest Hour," and "The Post" -- and more personal stories of marginalized people -- "Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri," "The Shape of Water," "Call Me by Your Name," and "The Florida Project," as well as "Mudbound," "Big Sick," "Lady Bird," and "Get Out." Last year's "Moonlight" upset suggests a strong Academy fondness for the latter kind of movie, but this year, oddsmakers are favoring the lavish, studio-backed epics by brand-name directors (especially Christopher Nolan's "Dunkirk" and Steven Spielberg's "The Post").

The acting categories are starting to look awfully monochromatic again, unless you think "Get Out" newcomer Daniel Kaluuya has a chance as Best Actor or that Best Supporting Actress has room for the likes of Mary J. Blige ("Mudbound") and Hong Chau ("Downsizing"). Otherwise, the top acting categories may consist largely of familiar Oscar-season favorites, including Frances McDormand ("Three Billboards"), Saoirse Ronan ("Lady Bird"), Meryl Streep ("The Post"), Gary Oldman ("Darkest Hour"), Daniel Day-Lewis ("Phantom Thread"), and Tom Hanks ("The Post").

In the end, maybe, it won't all be so grim and petty. Great movies and performances will be celebrated, and frivolity and excess will continue to adorn the red carpets. And then Hollywood will get back to its usual business of putting out extravagant fantasy blockbusters while reserving a handful of movies for grown-ups for the end of the year.

But the Oscar stakes remain high because the fight continues to be about not just who gets to put a shiny trophy on their mantel, but which stories get to be told and who gets to tell them. The entire process, from who gets to make decisions in the studio boardrooms, to who gets to produce and write and direct and star, to who finally gets an Oscar in March, is now under unprecedented scrutiny. Half of Hollywood has gone from being routinely belittled and ignored to having its stories paid attention to and taken seriously.

If we're lucky, the ultimate result will be a Hollywood that tells all kinds of stories, and a wide variety of people, not just one narrow demographic slice, will be able to look to movies for inspiration and see people who look like themselves treated on screen like they matter.

But the ride toward that Hollywood is going to be violently bumpy, and it leads right through March's ceremony at the Dolby Theatre. Buckle up.