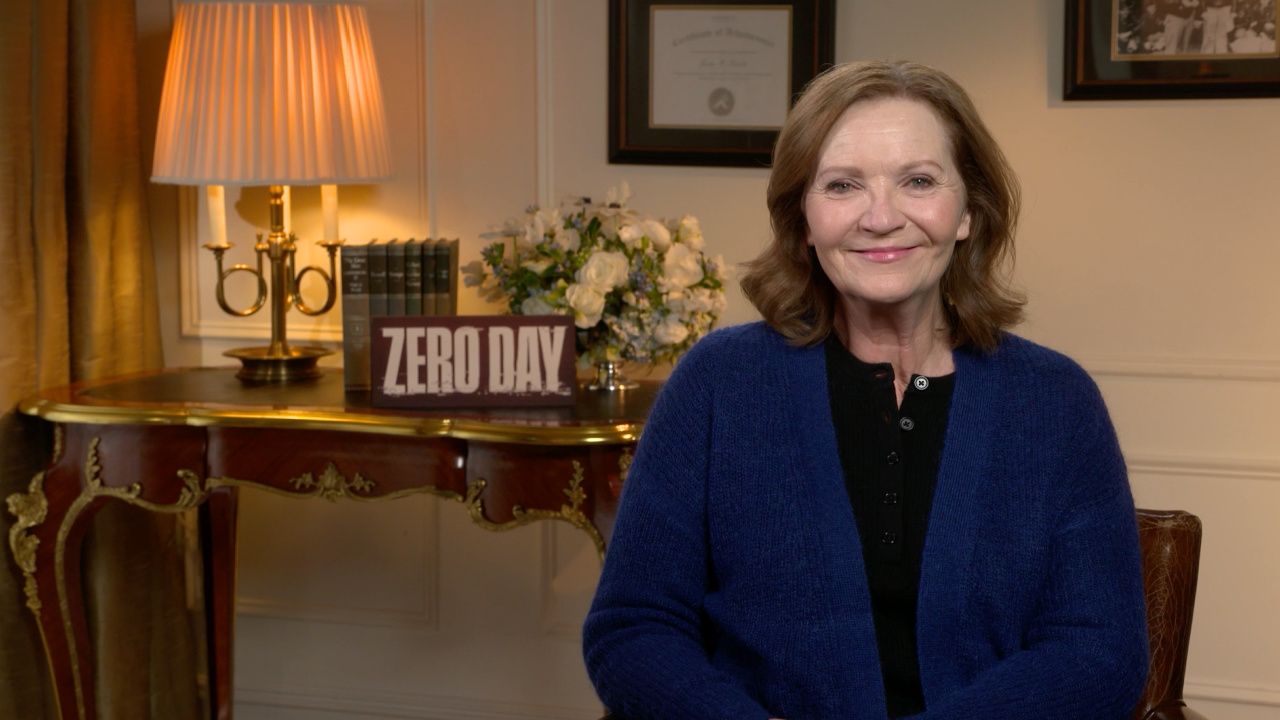

Kristine Stolakis talks about her new Netflix documentary ‘Pray Away’

The director talks about her personal connection to the subject matter, and how she approached some of the people featured in the film.

A scene from 'Pray Away,' directed by Kristine Stolakis

‘Pray Away’ is a new Netflix documentary from director Kristine Stolakis that covers the subject of conversion therapy. Specifically, the movie features former leaders from organizations like Exodus International and Living Hope who have renounced their past efforts, after realizing the harm that conversion therapy causes. Kristine Stolakis recently sat down with us to talk about her movie.

Moviefone: The movie's very powerful. What inspired you to tackle this subject?

Kristine Stolakis: Yeah, my uncle went through conversion therapy, actually, after he came out as trans as a child. So, he went through conversion therapy during a time when every therapist was a conversion therapist. This is in the '60s, before being queer had been declassified as some kind of mental disorder. What followed his time in conversion therapy was really poor mental health. So, he struggled with anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, addiction, obsessive compulsive disorder, all things I've learned are very common for people who go through this world. And he passed away unexpectedly before I went to film school, actually. So, I decided that my first feature would be about the conversion therapy movement, more broadly.

I started to do research and what I found that really surprised me is that the vast majority of conversion therapy organizations are actually run by LGBTQ individuals themselves who claim that they have changed, and they know how to teach others to do the same. And it was understanding that this is really a movement of hurt people hurting other people, internalized hatred, internalized homophobia, internalized transphobia wielded outward, that really helped me understand my uncle's hope. It was a very dark hope. It was a misguided hope, but it was hope nonetheless, that change was possible and that it was around the corner. And then, of course, his devastation when he could not change.

And then as I went on to make the film, we also weaved in the story of a survivor, of someone who primarily experienced conversion therapy from the point of view of a participant to ground the movie. And what is undeniable, which is the movement, deep harm, and trauma. So, that's the genesis for how the film came to be. And a bit about how we approached the subject matter.

MF: I saw that you have a background studying cultural anthropology. It seems like that really works to your advantage, because you hear, for instance, from Julie Rodgers, "This is where I went to meet other people like me."

Stolakis: Yes, yes. So, my undergraduate degree was in cultural anthropology and I definitely flirted with going down the route of becoming an anthropologist and getting my PhD and writing books. And I decided that I could make more of an impact through working in media.

But what I took with me was a real belief in a core concept of anthropology, which is called deep hanging out, the idea of really spending time in the world that you are filming. And when I spent a lot of time in this world, something that was very clear is that, and this might sound confusing if you are not familiar with this world, but for a lot of people, initially joining an ex-LGBTQ group, or participating in, you might not call it a conversion therapy peer support group, but some sort of conversion therapy peer support group at your church that might be called a Bible study on homosexuality, can actually provide a sense of community and belonging. And as time goes on, you learn that that belonging comes at a cost. And that is the dark part of this, is that you actually are not being fully accepted. You're being accepted on the condition that you will believe that being queer is a sickness and a sin, and that you will commit to changing in some way.

We wanted in the film to capture both parts of the reality of the movement, which is that for a lot of people, there is a feeling initially, especially, of belonging, and, undeniably, the movement causes trauma. I actually think that it is some of those good feelings that people have that keeps them in the movement for longer, that makes them commit more heartily to the idea of change. And for leaders, in particular, I think it is often those feelings of belonging that people mistake as change that makes them think, "Oh, change is right around the corner. I'm feeling great now." When really the reason they feel great is they're starting to form friendships. They're maybe kicking some kind of alcohol problem that they had that had nothing to do with them being gay. But they are getting maybe a sliver of mental health that they didn't have previous to this group.

But then the teaching becomes, "A core part of you is sick. A core part of you is sinful." And it's not exactly the message of change because we know that gender fluidity are real, sexual fluidity are real. The problem is the idea that something that is core about you is sick and sinful. That is the thing that traumatizes people, and that's why self-harm and, devastatingly, suicide are such a part of this world because you really are being taught to hate yourself. We know that youths that go through this and more than twice as likely to have attempted suicide in the past year. So, what you're picking up on, and I so appreciate you tying that to my own background, was a commitment to try to show that this is a full world, a full belief system. There are reasons that people participate in it. It's much more mainstream than you would think. It has a logic internally to it. And, undeniably, it causes pain and trauma.

MF: How do you go about reaching out to your different subjects in this and getting people like Randy Thomas and John Paulk and Yvette Cantu Schneider?

Stolakis: Yeah. So, for someone like Julie, in the film, the voice of the survivor in our film, we asked her to do a really hard thing, which was to recount the most painful and traumatic parts of her life in order to hopefully help others not go through what she went through. And her participation is pure courage happening in front of you in real time. And we had a lot of conversations about making sure we cared for her mental health in terms of how we were going to film with her. When we interviewed her, we did it over two days, and we really consolidated the hardest questions in the first day, which she knew so that she could organize support for herself around that first day. And then the second day, we jumped around in terms of a timeline of what parts we were going to cover of her life, but it was the happier staff, so she could feel prepared and comfortable.

And I would say that for all people in the film, there were open conversations about how their participation would help in our collective goals and the movement. And also open conversations about our intentions, with how we wanted the film to really encapsulate this idea of people hurting other people, to help shine a light on how power works in this world. For the former leaders, that meant a shared understanding that we would interview them and have them be a part of the film with complexity, with nuance, but also with accountability for the fact that they did cause harm, even if they had good intentions. And I think that openness actually engendered a lot of trust, which people I think may assume isn't true, that you have to pull the wool over someone's eyes in order to get them to participate in the film. And that's not been my experience at all.

And that was also true with Jeffrey McCall, the person in the film, who is a current leader of an ex-LGBTQ organization, who in the world of today, you might see as a de-transitioner. He is someone who we were very forthright with, that we needed and wanted a voice of a current leader in the film to show how the movement continues into today. And we promised to not put words in his mouth, which I felt very comfortable not doing because I know that gender fluidity is real, and I do not question that he no longer views himself as trans. And I really disagree with the consequences of his actions. I think the fact that he's sharing his story and putting forth the idea that trans is a sickness is that it's very damaging, and I know that to be true, and he and I disagree there.

But the fact that I was honest, that we would include critical voices in the film, I think made him trust the process. He knew where he fit in a bit. And I'm thankful to him for participating, even though we, again, really disagree about the consequences of his actions because far too many people practice it in the dark.

That's a summation of the way in which we got people to participate. And it was a tender, complex process, especially because I'm someone who came at this having witnessed the very real trauma of someone that went through this, which I also was explicit about. So, that's a sum-up of how we got people to participate.

MF: With someone like Jeffrey, and a couple other of the former leaders kind of bring this up, you get the sense that this movement really is, maybe, coming from a place of love. But we can stand outside that and say, "You might think it's loving, but it's really harmful." Where do you fall on the question of whether or not that's a justification? Are they being honest about that? Or is it some of both?

Stolakis: Well, I think that most people in this world start with good intentions and truly believe that they are helping people. And I actually think that is part of the reason the movement continues today because it's fueled by misguided good intentions. And that means, for a lot of people, also fuel for a lot of denial. Denial in terms of their own feelings of the language of this world, their own same-sex attractions, for example, not going away. It lends to a really dark denial of not listening to the stories of survivors who say, "This is causing me pain. This is causing me trauma." People have an easier time ignoring those people if they believe they're doing the right thing.

So, that was something we tried to capture because a huge message we want to put forth in the film is that as long as homophobia and transphobia continue in mainstream churches and conservative communities across our country and world, there are going to be people who are motivated to believe that change is possible. And some version of this will continue. So, these messages aren't coming from nowhere. It's not a random few bad apples who are leading these organizations, harming people. It is a system of power led by people who are hurt, who have internalized extremely damaging messages and then do very damaging things.

So, for me, the most important thing to capture in the film was that larger culture, that larger structure of hate and power that can make this movement continue into today. And to your point, I think it is fueled by good intentions, which is a problem because those intentions, unfortunately, and the subsequent actions, they do cause harm.

MF: As a viewer, one of the most powerful images is, after hearing Julie's story and about her self-harm, seeing her on her wedding day with the sleeveless dress, with her scars on display, and they’re just a part of her. What was that like for you as a filmmaker in that moment?

Stolakis: Yeah. So, a part in the film that touches a lot of people is Julie Rodgers' wedding day, where you see her scars that are the result of self-harm, on her arm. She continuously burned herself over and over again in the same parts of her arm. And the day of her wedding, she wears this sleeveless wedding dress, and they're on full display. And I feel two really strong emotions when I think about having witnessed that moment, which is one, the devastation and realizing that this is a trauma that will never fully leave her. And I felt a sense of hope and beauty that she is someone who left this world and has found people and a community more generally that love her exactly as she is, with no caveats, with no need to trade any part of herself in for love and belonging.

For her, in that moment, it was in a church. Doesn't have to be in a church. It can be at a brunch with friends, it can be on a walk in your neighborhood park with your next door neighbor. Love and belonging can look like a lot of different things. And what I want people to know who are LGBTQ and who are in this world, is that you can have a full life of love and belonging outside of it.

So, that for me was that moment. It's really not about the wedding. This is not a rom-com happy ending thing that we were trying to pull off. It was all about ending the film with the idea that there are places that will fully love, accept, and really fight for LGBTQ people. And people that are in this world, that the message that that's not true. And that's a lie. It is true. There is life on the other side of this. And we wanted to show that in the film.

MF: I felt like Julie's choice also shows her acceptance of that part of herself, and that she doesn't need to wear something to cover that up. As if she’s decided, "This is who I am, and I'm not ashamed of it. And I love myself. And it's just a thing that I did. And it's okay."

Stolakis: I love that you said that. And that's something I've said in some interviews, but I didn't say it here. That yes, community can also come in the form, I think of self-love, of being our own best friend, and in our private moments, telling ourselves, "You are wonderful as you are." And that is also something I absolutely felt in that moment of the wedding. That Julie made a choice that's so beautiful, which is to say, "This happened to me, and I am going to celebrate my full self today, scars and all."

And I think that a really hard part of this world of conversion therapy is not just the practice, it really is a movement. It's an entire belief system of books, conferences, famous Christian superstars that you look up to, hashtags, social media accounts. You can surround yourself with a message that to be LGBTQ is sick and sinful, and you can surround yourself with this dark hope that change is possible. And that entire culture can get into your bones in a way that it presents in your most private and intimate of moments.

So, what can we do to combat that? Well, many things. One of the things, I think, is to try to find a way to love yourself when you're alone. Two, to truly love yourself in solitude. And, unfortunately, I've seen the fact that in solitude, sometimes, this is when people feel it the most. When they're praying, when they're journaling. And that is why, again, self-harm and, devastatingly, suicide are such a part of this world because if you're taught to hate yourself, you're going to do it 24/7. So, then to see someone that loves themselves fully as they are, it's very powerful. So, I do hope that people go into the film understanding, of course, it's a very heavy topic and there really is hope on the outs for people that are in this, that they can leave.

'Pray Away' is now on Netflix.