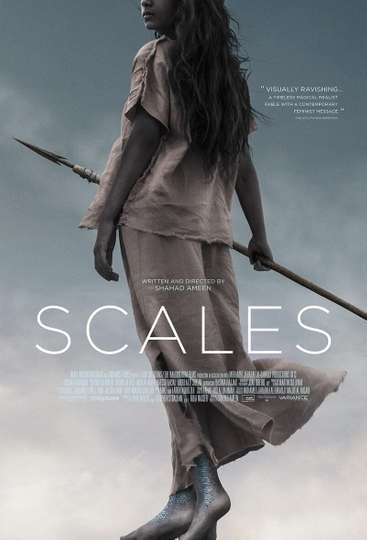

Female Filmmakers in Focus: An Interview with ‘Scales’ Director Shahad Ameen

This week, writer-director Shahad Ameen talks about her feature film debut ‘Scales’ and recommends the directing work of Julie Delpy.

Scales directed by Shahad Ameen

(L) 'Scales' director Shahad Ameen. (R) Basima Hajjar as Hayat

Shahad Ameen was born and raised in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. She earned a degree in Video Production and Film Studies from the University of West London, as well as a degree in Screenwriting. Her short films have played in numerous festivals around the world.

Her feature film debut ‘Scales’ had its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival in 2019 as part of the Critics' Week sidebar. The dystopian feminist film was selected by Saudi Arabia as its selection for the 93rd Academy Awards, although it was not nominated.

The film follows a young girl named Hayat (Basima Hajjar) whose fishing village is governed by a dark tradition: each family must give one of their daughters to the creatures that live in the sea. Hayat becomes an outcast when her father saves her from her fate as a baby.

When she hits puberty, she notices changes in her body and finds herself drawn back towards the sea. A stark condemnation of the ways in which society teaches girls to hate their own bodies, ‘Scales’ is sure to linger in the minds of viewers long after it concludes it’s brisk 74-minute runtime.

‘Scales’ is in theaters in New York and Los Angeles now.

Scales

Hayat, a 12-year-old strong-willed girl, lives in a poor fishing village governed by dark tradition, in which every family must give away a daughter to the sea creatures... Read the Plot

Ameen sat down with Moviefone to talk about her new movie.

Moviefone: What was the inspiration behind this story?

Shahad Ameen: The story came to me a long time ago. It was first a short. It’s so funny because I never thought I would write my first feature about mermaids. I just had this image of this mermaid being chopped in half on screen and a girl seeing a creature that looks exactly like her being harmed by her father.

After I finished the short film, I felt that it was such a missed opportunity. In the short film, the father is the one who kills the sea creature or the mermaid, and the daughter is the one who is watching. I wished it had been the daughter who did that. I wished it had been the daughter who hates on her body, on herself.

From that I decided I would do a feature. That was not the end of the story. So I wrote the story of the feature for it to be a journey between Hayat and her body, a journey between Hayat and herself, her accepting her body.

MF: Do you think Hayat was suppressing her true nature in order to be more like the men?

SA: I remember when we were little girls, if I were into sports or if I were into certain things that girls are not supposed to be into, our solution for it, me and my friends when we were like 12, was that we wished we were boys. It’s much easier to be a boy in this society. Why would you want to be a girl when all the fun things boys get to do. From that the idea stemmed.

The idea that you know when you get your period suddenly your muscles are weaker, and you don’t understand how to deal with that and your only solution is to suppress all of these emotions and not understand what is happening within you. And you say to yourself, “someone else has it easier, why can’t I be like them?”

That’s what Hayat does. Her body is telling her she doesn’t belong here, to go somewhere else. But she keeps refusing that message and refusing the idea that she has to be at peace with her body, and unlearn what society had taught her about her body.

MF: Can you talk about the relationship between Hayat and her father, and why you focused on a daughter and a father rather than a daughter and a mother?

SA: I wanted the mother to be programmed. As soon as she lost Hayat as a baby, for her that baby died. Sometimes I feel that women are the ones that hold on to traditions of a society. They hold so tight to it because, I feel, that they gave more for it, and they sacrificed more of their life for it, so why should they give up when they’re already older, and they’ve already believed in and already sacrificed for it.

That’s how I wanted to show the women in the village. They’ve already sacrificed, they've already given kids to the cause, so they will fight for it the most. I thought that the only one who can rebel against it is the father.

For me, I always wanted the film to start with a father calling out to his daughter Hayat, meaning life in Arabic. And I wanted it to end with that. It was always about a father choosing love over tradition, choosing life over death, and choosing his daughter over his village.

MF: What do you think is so alluring about mermaids?

SA: I had never really thought of mermaids until I wrote these stories. I was writing something about a mermaid and was like, “what is a mermaid?” Doing research, I found out that in Middle Eastern mythology they believe that it's an Assyrian goddess. She’s the goddess of fertility who had fallen in love with a human person, and then she had killed him by mistake, so she had committed suicided.

To preserve her beauty and her wisdom, the gods made her into a mermaid. I was like, what’s up with those gods? She didn’t ask for that! They forced her.

You’re not allowed to die on your own terms. In a way I felt it was kind of a punishment for her being free and that’s where the idea came to be. Even though she was alone in the water and isolated, she’s free. From there, I thought maybe I could create a society where all the free women are out in the water.

MF: I was struck by the black and white cinematography. It's a stunning shade of gray. How did you achieve that look?

SA: We didn’t shoot in black and white, actually. We shot in color and in the editing process and post-production process, when we got to the final cut we decided what if we turned the film into black and white.

The colors were still not giving me the impact I wanted, which was a very harsh contrast. A very harsh contrast between men and women. A very harsh contrast between the sea and the land. Once we switched the film to black and white it gave us that dryness, it gave us that timeless quality that the story of the film is set in.

MF: How did you scout the locations?

SA: I love that you’re asking that. So we shot in Oman near the Strait of Hormuz. It’s a place filled with mountains and immediately on the water. It took us a while to find it.

For a while we thought of the Dead Sea, so we thought we’d shoot in Jordan in the actual Dead Sea. What is beautiful about it is there is a lot of salt left on the sand. But the problem in Jordan is because there are no fish, there are no fishing communities. So we went to the Gulf region of the Arab world and thought maybe Oman. When I went to the location we shot in, I was so mesmerized.

We kept going back for almost two years to that same location, just making friends in the community. What you see in the film, all the extras are the actual people in the community there. The fishermen are actually fishermen. That was amazing just being able to shoot in Oman in that location.

MF: In particular, I loved that cracked sand towards the end.

SA: There was a place where someone was building something and it had this very small area where there was cracked earth. We thought, fantastic, we will shoot there. It was small, but it was going to get that effect. Then on our last day to shoot we were supposed to shoot that scene and then the AD comes to me and says they’ve destroyed it, they’ve covered it. A panic came to me. I thought maybe we could do it with VFX.

Then our location guy went on a ride, he found the biggest cracked up earth, better than what we had originally had. It had just rained, and the water had dried. It’s not a sea. It’s not a lake. We don’t know why it’s there. It was just put for us. It spiritually knew that we wanted to shoot there.

MF: How did you cast Basima Hajjar as Hayat? Her eyes in particular I thought were really piercing.

SA: Right? Oh my god. Basima, I’ve known since she was very young. When I came back to Saudia Arabia, she was acting in commercials and stuff.

I knew her through ADing a couple of commercials. I became friends with her mom and I wrote a short film called ‘Leila’s Window’ and I asked her to act in it. It was five minutes long, and she did a fantastic job, and I couldn’t get over her eyes. All actors' eyes move at normal speed. Basima’s move in slow motion. I don’t know how, maybe it’s very vague, but she has such a soul.

From the first film I did with her, she was definitely my muse. I did with her the short films ‘Leila’s Window’ and ‘Eye & Mermaid’, so for the feature film of course it was her from the beginning. We were going to lose her two weeks before the shoot for exams. They kept sending me other girls, but I kept thinking, “they don’t have Basima’s eyes!” I’m very thankful you mentioned her eyes, because that was my argument to keep her.

MF: What do you hope people take away from the movie in the end?

SA: It’s a story about life, about the sanctity of life and how it’s more important than tradition or culture. When you have to choose, you have to choose life.

MF: Can you recommend another film directed by women for our readers to seek out?

SA: The person who came to my mind is Julie Delpy. She’s a French director I really like.

MF: What’s your favorite from her?

SA: I think ‘2 Days in Paris.’

2 Days in Paris - directed by Julie Delpy

Director and star Julie Delpy in '2 Days in Paris'

Perhaps best known for her three decades of acting in film, including generation-defining turns as Celine in Richard Linklater’s ‘Before Trilogy’ - for which she’s also received two co-writing Oscar nominations - Julie Delpy is also an accomplished director.

After the completion of a few short films, Delpy made her debut with the comical romantic farce ‘2 Days In Paris’, for which she received a Best First Feature nomination at the Independent Spirit Awards.

She followed that up with five more feature films, including ‘My Zoe,’ which was just released earlier this year. Currently, Delpy is developing a television show for Netflix called ‘On The Verge’. Set in Los Angeles, the show will follow a group of women navigating life in their forties.

2 Days in Paris