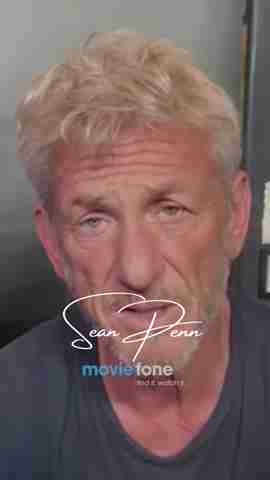

Joel Edgerton Urges You to See 'Loving' and Question Your Role in History

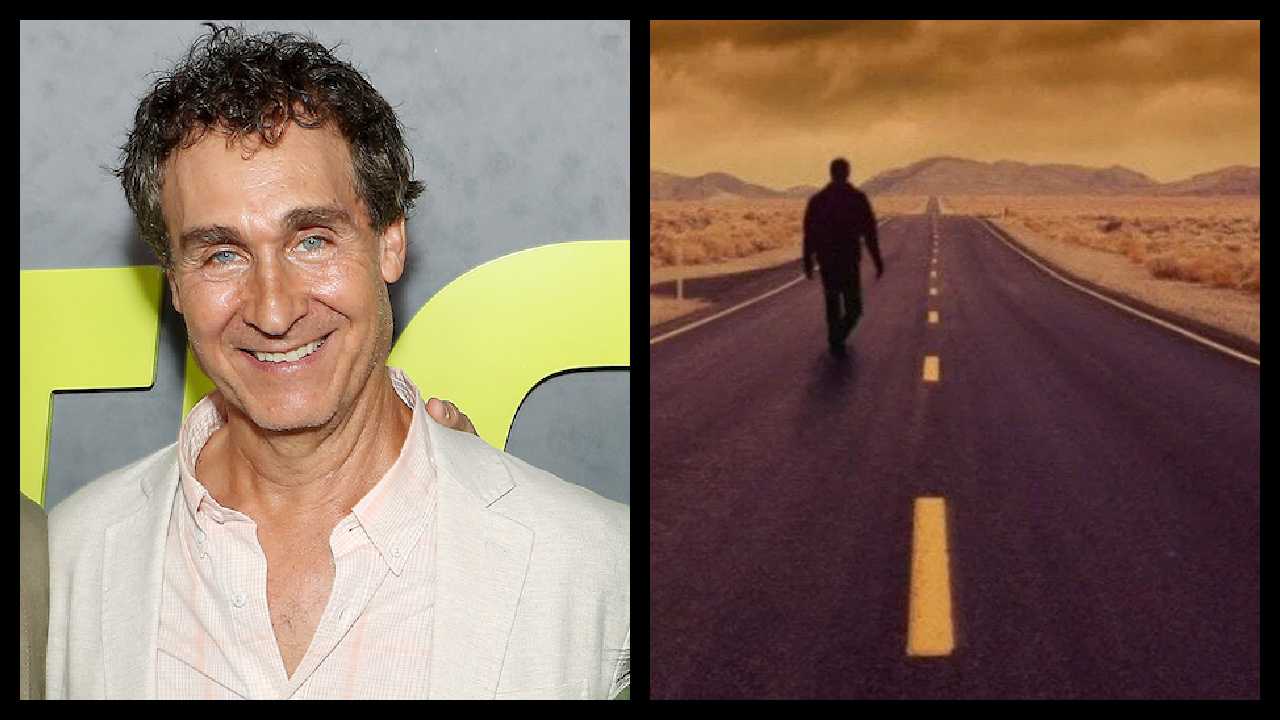

Taking on a real-life character is a challenge for any actor; but tackling a real-life character who changed the course of history for an entire nation adds a ton of pressure. Joel Edgerton's portrayal of Richard Loving, in writer-director Jeff Nichols's "Loving," is what happens when an actor gets it right.

"Loving," based on the 1967 Supreme Court case, Loving v. Virginia, which voided all anti-miscegenation laws in the United States and made all interracial marriages legal, skirts the "based on a true story" grandiosity, making way for a deeper, quieter look at the lives of Richard and Mildred Loving (Ruth Negga).

We got a chance to sit down with Edgerton recently to talk about his portrayal of Richard Loving, his insight into the American political climate, the part we all play in prejudice, and the possibility of an Oscar nomination.

Your character, Richard Loving, is more of a quiet man; there's little dialogue, it's more in your body and face. How did you prepare for something like that?

We actually have a lot of footage of the Lovings because Nancy Buirski's documentary, "The Loving Story," really tells the story of them -- the second half is really about the court case. In the first half, we see Richard and Mildred at home, interacting together and with the kids. Then she sent Jeff this kind of archival footage; there was so much she couldn't put it all in the documentary. It gave Ruth and I a chance to check out all the external things, like how they walked, the posture, the sound of the voice. Of course, that gives you enough to get to a point of mimicry. The real question is about investigating between the lines, between the couple, what was going on between the two of them. What was it that they felt for each other, and also, what were Richard and Mildred like when the cameras weren't pointed at them, because they're both very shy.

I actually went to bricklaying school, you know, because Richard was a bricklayer and I thought I'd save Jeff time on set by not standing there on the day going "Ah, so what do you call this, and where do I put the brick?" But it informed so much about posture and, on a sort of a weird parallel to a metaphorical level, gave an interesting sort of analogy, I guess, to the bearing down pressure that Richard was -- really, he felt weighed down by this. Mildred was the one who had that sort of steel rod in her spine. So, a lot of looking and investigating and listening and you know, trying to hit that center of the dartboard that Jeff wanted in terms of accuracy.

But, he's the real hero, Jeff, because he was the one observant enough to craft the screenplay that really paid homage to the two of them and really spelled out what, really, love is between certain couples, that it isn't about overtures of love, that it isn't about sex scenes on film; it's about that silent stuff that goes between two people.

Were you able to shoot on location?

Yeah, we shot in Richmond.

What was your experience living and working there?

It was pretty special. It was very special to shoot the movie where the story took place. It just does something extra. It has an extra charge to it. We shot in the courthouse, that's still standing, and hasn't really changed at all -- that first courthouse, where they were told "Go live somewhere else." We shot outside the real jail, where Richard and Mildred were kept, and visited inside the jail -- we didn't shoot inside. We visited the graveyard where they're buried, and it just gave us something extra by being there. Beautiful place.

Being that you're actually Australian, and this is about an American story and court case, when you took a look at the script, what was the first thought about this particular case that actually happened so recently, as far as history goes?

Right! It's so recent, it's so -- it feels like -- wow, this happened 50 years ago, and yet, you also look at different corners of the world and here, and go -- "Uh, it's really still going on." The same issues swirl around, and at different times they become hotter topics than others. But, as Jeff points out, equality is not something that we will one day solve and then move on. I think we always have to be mindful and we always have to find new ways to keep the conversation at a place where we can all listen, and to drag it back from the intensity. Because the intensity causes confusion and violence. But, you know, I never knew about the story.

The first person who told me about Richard and Mildred Loving was Jeff Nichols, and I was like, "Oh, yeah, that makes sense. I'm off the hook, 'cause I'm Australian." But then, not very many American people -- particularly white American people -- knew who Richard and Mildred were. A lot of young African-American kids came up to me since making the film and they're like, "This is my mom and dad's story," or, "This is my uncle's story." But I really hope, apart from the sympathetic people who have the empathy or connection to the story in their own life, the people, like me, who have a very smooth, middle class, never-experienced-injustice kind of life come to see this movie, because it's about welcoming people in to have an empathetic experience with two people.

Richard and Mildred represent, to me, anybody that suffers judgment based on otherness. I think Jeff invites you in to watch them just be people, living their lives, up against a big obstacle. Come out of that film and I challenge anybody -- I challenge people to then go, "Where does judgment live in my brain? How does that affect other people, and how can I maybe re-examine that?"

How did it change your perception of this country in general? With this story and what's going on in our political climate right now, how is it making you view the U.S. in general?

Well, I think all democracies are interesting, because obviously democracy is -- we just assume everybody has the same rights and freedoms. But they really don't, when we're all balls down and you really come to take apart all the pieces of it. My country is not that dissimilar. I think most people are generally pretty apathetic when it comes to politics because life's pretty crazy in Australia, but we're still not there on gay marriage, which is very shameful.

We have our own complicated racial history and racial tensions that exist today that are not that dissimilar. We don't have a history of open slavery as existed in America. But I'm very fascinated by that aspect, cause we don't have that in Australia, the African-American experience and the civil rights timeline. I just recently watched "The 13th," the documentary Ava DuVernay made, and I learned more from watching that, you know, about prison systems.

Look, I love this place, and this place provides a lot for me, but I also realize that it's a hard place for a lot of people to live, and, in general, sometimes that relates to the color of their skin. I don't truly believe that, under the democratic system that you have here, everybody gets the same shot at the target.

Would you say it's changed your view on racial relations as a whole? I only have experience here in the States, obviously, but you travel often, so you've got a wider view. How has it changed your mindset?

You know, I feel like I've always been a pretty liberal and open-minded person. I think what it's really done is made me really slip into the shoes of someone else's life. I think I saw things more through a window before, and by experiencing Richard and Mildred's life -- it's not to say that I'm now inside the room, but I have more of an empathy for what it might be like, for example, to be in your bed and have your door knocked down and to have the Sheriff come into your bedroom, to be constantly harassed in a way that other people wouldn't, purely based on the way you look or where you're from.

Also, in terms of the stretch of the entire timeline of slavery to where America is in terms of equality and rights for African-American people, I just find this deep sadness about a group of people who were essentially kidnapped, brought somewhere they didn't really want to be, struggle to become free, and then really still have not been handed that right through a series of complicated and difficult legal and political kind of social situations. Essentially that's still -- that situation has not been resolved. And I think that's f*cking awful.

There's somewhat of a trend going on, especially with films like "Loving," "12 Years a Slave," and the popularity of "Hamilton" is that, lately, we're really focused on history. Do you think there's something positive that could come of people watching art based on the past?

I wonder if sometimes time allows the truth to be told. I know when I was in grade school, elementary school -- grade school? I recall -- and I may be just imagining this -- that we weren't really told the full truth about the history of, say, European settlement in Australia. Yet, now I feel like that truth is told more and I wonder if the distance of time allows people -- because it's the next generation, or the generation after that -- [to acknowledge] what happened years ago, whereas the people responsible at the time probably experienced a lot of shame.

I think when change happens, too -- I've thought a lot about this -- when change happens, the people that stood in the way of change become the villains of the story. But it's amazing how, when change does happen, everybody stands on the side of change and goes, "Yeah, that's what I wanted, too!" But I think it's good that the real narrative gets told, even if it is generations late, especially if it has a connection to what's happening still today, because then it's not just a period piece; it's kind of a -- it's a mirror to current events.

There's a lot of Oscar buzz going around. Does it add a little bit of pressure?

It adds a bit of pressure to me. I always worry about -- that it would allow me to buy a ticket to my own parade, you know what I mean? Because that sort of talk does definitely stroke the ego, and I have to acknowledge that, accept that on a bigger picture level. It's great for us, being a small movie.

I know what it's like. Most of the movies I make are very small, and it means you don't have the money to really push them out into the world. What you're hoping for is that they catch fire. To have that scrutiny on it in terms of this as a smart, special movie that might be nominated for awards, that means that there's more publicity out there, that there are more eyes and ears interested in the movie. So, on a personal level, that's a different story, but on a macro level, it's pretty cool.

"Loving" opens November 4.