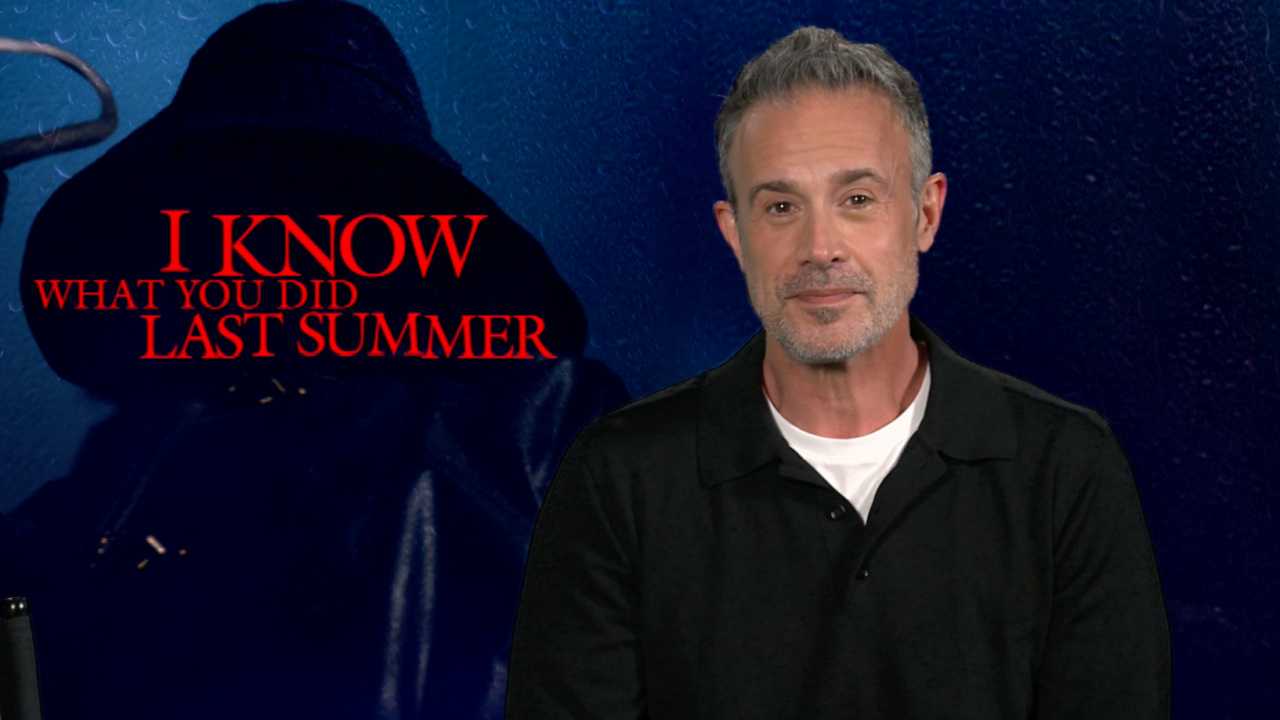

Bryan Cranston Loves His 'SuperMansion' Superhero -- and Would Play Walter White Again

Sure, you're following all of the Marvel- and DC-related comic book superhero shows, but if you're not watching "SuperMansion's" League of Freedom, you might be missing the funniest -- and maybe even the most poignant -- take on the cape and costume crowd.

As the stop-motion-animated series returns to Crackle for a second season of misadventures from the over-the-hill, dysfunctional crimefighting team, co-creators Robot Chicken") joined leading voice actor and executive producer Bryan Cranston for a press roundtable tackling an array of predictably silly surprisingly deep subjects.

What do you bring of yourself to this character?

Bryan Cranston: I don't need boner pills! Let's get that out there! You know, it's similar to doing live-action, in the sense that when an actor takes on a character, it's a marriage of words and ideas to what the actor's sensibility is, and you find where that is. There are times when I'm directed to punch certain things, and I go, "Oh, yeah, I see! He's more upset at this point."

And then, there are times when I bring in my own personality and they go, "Oh, that's good! Let's go on that track!" I'll do certain things or make certain sounds that the guys will respond to and go, "Oh, that's good!" Early on, as we were feeling through the character, I think it was Zeb that said, "I don't know, it just feels better when he's really angry. He's just really upset." And then I have to figure out why.

It's because he's losing his sense of relevance. He feels it slipping away, so he's desperately clutching onto these things. That made it easier for me.

It doesn't matter if it's animated or live-action, you're still developing a character, you want to be consistent with that character and you're contributing to the storylines. It's as engaging as live-action development.

Did you have to learn a lot about the superhero culture, tropes and references for this?

Cranston: I've never been a comic book guy, so I look at it just from the justification of the character's emotional sense. What does he want? What does he feel? Who does he want to be around? What is he losing? Who is he afraid of? That always mixes in fine. The more you humanize superhero characters, the more they're relatable. The more they have a vulnerable point, whether it's emotionally or their superpower, or whatever, we relate the superpower or the loss of a superpower to their emotions. It's just fun to walk through that.

Zeb Wells: And it was important to us that you didn't have to know a bunch of comic book superhero references to find the jokes funny. We wanted the characters to be funny in their interactions and have very human conflicts, and have that be the basis of the comedy.

Matt Senreich: You have these insane superpowers, but that's irrelevant. It's about humanizing them and grounding them in a way that we can all relate to.

Matt and Zeb, what made you think of Bryan for this role?

Senreich: We were afraid to ask him. We wrote the part, and in the script, it says, "A Bryan Cranston type." We had our buddy, Seth Green, play the part for the temp animatic, and we realized that voice wasn't good. He just turned to us and lectured us on how we're very chicken and we should just reach out to Bryan.

To Bryan's credit, we sent him the role and within 24 or 48 hours, we got a call back. It was beyond flattering. He was like, "I don't want to just play this part. I want to make this show with you." It just took off from there.

Cranston: For me, if it didn't have an interesting story to it, I wouldn't be sitting here. But the idea of a household full of superheroes who are perhaps past their prime and trying to hold on to what's left of their dignity and abilities appeals to me. And having sequences where the superheroes go shopping and do household chores was a really good idea.

What did the success of the first season give you permission to do with Season 2?

Wells: It was seeing how well exploring the humanity of the characters ended up working. With the second season, we could push the drama a little bit and trust that the characters we'd created and that the actors helped us create would make those situations funny.

So if you look at Season 2 on paper, some of the episodes would sound more dramatic and that the stakes are a lot higher, but they're all just as funny because we still have this band of idiots. We were really able to take the brakes off and do high-stakes superhero adventures. It's really fun.

Senreich: We saw how pairing certain characters together worked or didn't work, in certain ways, and what conflict built from their politics and their boyfriend-girlfriend relationships.

Does animation give you an advantage in discussing controversial topics that live-action does not?

Senreich: Yeah, I think you can get away with a lot more animation than you can in live-action. I come from the comic book and action figure world, where violence is funny in animation. When you go back to Tom and Jerry, it plays a lot better. If you see those things in real life, you're going to be taken aback. It allows you to over-dramatize certain relationships to get to that point you want to make.

It just allows for you to push the envelope a little bit more, but it's dangerous to go too far. It's about always knowing where that limit is. There are certain topics that are too far, so it's about where is it too far and how do you make it funny while at the same time not, and also teaching a lesson while going through a situation like that. It's a tightrope that you walk, and as long as you're aware of it, you're allowed to do a little more with it.

Matt and Zeb, how long have you guys worked together?

Wells: Off and on, for 10 years now. We've known each other longer.

Senreich: I found Zeb when I was working at a magazine called Wizard, back in the day. He entered a VHS video competition. I was probably 25, at the time, and Zeb was 20. He won that competition, and I just stayed in touch with him 'cause I thought he was a talented fella. And then, when Robot Chicken started up, I brought him on to write with us, and that was since Season 3. We've just been goofing around, ever since. It's been a nice romantic interlude.

Cranston: Matt is really one of the bosses -- and he brought on Zeb to take over this show, and even though the guy who brought on the guy doesn't agree with everything, he gave the power over to Zeb to say, "You know what? You're running the show. You're the showrunner, so go and do what you think is best." That's pretty remarkable.

Wells: We try to run it like a relationship, where it depends on how passionate either one of us is about something. If it's keeping Matt up at night and I just think it's a slightly bad decision, I'll just let him have it. And that goes both ways. The real problem is when we're both equally passionate. Then, I don't know how we solve it. Whoever is more stubborn wins.

Senreich: When you know someone for as long as we've known each other, it doesn't feel like there's ever a wrong way to play it out. I do believe in the people that I work with. I'm friends with these people, and I know that's a dangerous thing and people say not to do it, but I like going to work and smiling every day. I don't want to work with people I don't like.

Titanium Rex is searchingfor relevance as he gets older. You, ironically, have become more relevant later in life, Bryan.

Cranston: Try telling that to my wife! Art business is a little different. It's a little different. And I'll say for men, too. It's different for men. There's more opportunities for men. There really is. So I'm certainly the recipient of that good fortune, and I'm appreciative of it. Had it never happened, I'd still be a working actor and be fine, and not know what you miss.

I don't think life or this business owes me anything, so you reap what you sow. If you work hard, you have a better chance of producing something that you're proud of. If you don't, you won't. And it's really simple. Ask Warren Buffett: "All right, Warren, what's your secret?" He goes, "Well, just make more right decisions than wrong ones." I swear to God that's what he says. You go, "That's it?" He goes, "Yep, that's it." Wow. Make more right decisions than wrong ones.

And it's like, yeah, I think all of us try to do that every day. And that's no different. This is what we try to do at work. We think this is the strongest choice. We're not positive. We think, OK. Then it comes to us, and we're reading it, giving notes, or reading it in the booth doing it. Then some suggestions, and they'll take two or three different ways of doing something.

Wells: Or if we were unsure about something ... Sometimes an actor saying, "This doesn't feel right to me either." That's happened with Bryan, it's happened with Yvette [Nicole Brown]. Then you're like, "OK, I had that in the back of my head that that might be wrong. If you think it's wrong as well, then let's sit down and change it." And you have to be open to that. You have to be open to the happy accidents and discovering that stuff, where it doesn't feel as alive, and you're missing out on great stuff.

Bryan, your "Breaking Bad" co-stars Aaron Paul and Betsy Brandt told me recently that if there's any downside at all to be a part of that series it's the high level of work that you got to do, making it hard to decide what to do next. Do you feel that way when you thought about what the projects were going to be?

Cranston: It's a nice, difficult position to be in. Yeah, the bar was raised with the quality of writing on that show, and you want to see if you can match that anywhere you go, and I do. I want to make sure that what I do has specific purpose, and not just throwing a dart at something to keep busy.

This is an example of just that: that good storytelling doesn't have to be in the form of the classics. It doesn't have to be revered by everybody. In fact, to me, the best storytelling is not universally loved by every single person. And to me, I think you water down the efficacy of the work itself.

Is there any chance we're going to see Walter White on "Better Call Saul"?

Cranston: I don't know. You could. I actually think it'd be fun. I have not been approached by it. I know that Vince [Gilligan] wouldn't do anything that would damage the overall brand that he's worked so hard to develop on a stunt-cast kind of thing. Then I think, "Well, what if it's just a brush-by? If it's just two guys in a market. Are those ripe? I don't know." We don't even register that we knew each other three years before we see each other again. That's life.

It's actually very honest. It happens. So the bottom line is, I would do it in a second. If Vince wanted me to be on the show, I'd be on the show.

What's been the unique pleasure of doing this show, distinct from the "Robot Chicken" experience?

Senreich: For me, "Robot Chicken" is a sketch comedy show. It's "SNL" using action figures. It's always been that, and we always laugh, because if you look at the staff of "Robot Chicken," my first sold scripts were dramas with Geoff Johns as my writing partner. Zeb comes from the comic book world and was working in comic books for a while. We have two playwrights. It's like, very odd selection of people who have worked with "Robot Chicken."

But this lets you tell a story where you actually can sit down, and it puts us back to our roots where we're like, "OK, we can actually find characters, we can go into their history, we can deal with their relationships," and that's something that we've always loved to do.

Wells: For me, there's an animatic for a later episode, and it's a scene between Jillian [Bell] and Bryan. And we were watching an animatic, and I got choked up watching it. It's like, "That's not supposed to happen in the Stoopid Buddy Stoodios, watching an animatic for one of our shows!"

Cranston: That happens to you when you watch animated porn, too.