'Lost City of Z' Director James Gray on the 'Uncomfortable' Making of the Movie

Get ready for an adventure.

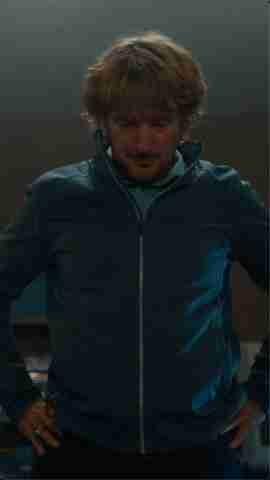

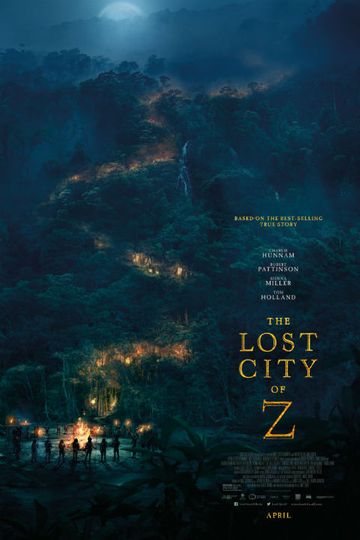

James Gray's "The Lost City of Z," expanding nationwide on Friday after opening in limited release last week, is one of those classical tales of obsession and damnation. In 1925, after several previous trips to the area, British explorer Percy Fawcett took his young son into the Amazonian jungle in search of a supposedly advanced indigenous tribe, never to be heard from again. The movie, based on New Yorker science writer David Grann's immaculately told nonfiction book, is a thrilling expansion of that story, anchored by some of the greatest performances of the year (Charlie Hunnam is Fawcett, Robert Pattinson is his trusty sidekick, Sienna Miller is his wife, and Tom Holland is his young son) and some of the finest photography (courtesy of Darius Khondji and actual 35mm film) you're likely to see ... ever.

Much like Fawcett's tortured journey upriver, the film had a number of production starts and stops, first when the film starred Brad Pitt and again when Benedict Cumberbatch took over the main role. For a while, the movie looked like it would never happen, but was suddenly brought back to life with a new cast and James Gray (who also wrote the script) still at the helm. But no matter how hard it was to put the movie together, it was even harder to shoot, with the crew venturing into the jungle (just like Fawcett) and facing all manner of complications.

I got to sit down with Gray in Los Angeles to talk about the movie, just what happened while they were shooting, why the leading men dropped out, and whether or not he'd ever direct a Batman movie.

Moviefone: You've been working on this a long time. What about that David Grann story really excited you?

James Gray: There's a great thing I once read in this interview with Stanley Kubrick, where somebody asked him what interests you in a story and he said, "Well, it's sort of like asking why you married your wife. She has a nice face and a nice figure. But there are a lot of women with a nice face and a nice figure, you can never really put your finger on it." So there's a little bit of that. But also it's weird because it's maybe not what you would think.

What fascinated me about the story was a very small passage in the book which was about Fawcett's father. The guy was a well-heeled person and was in the top social circles in England and gambled away two family fortunes and drank himself into the grave. So I thought, That's interesting. Then I thought, It would be interesting to make a film that's not only about the nobility of the idea of exploration but also that it was a form of escape from a world he found hostile. That was a very powerful dual motive. You can't really film motive, but you can film context. I thought that was interesting because I could understand that. I empathized with Fawcett's insecurity and the bad position inside the top social circles in England. So I said, "That's something I can latch onto, that's something powerful to me." And everything really sprang from that.

It wasn't so much the adventure aspect although that's catnip to a movie director in some ways, also terrifying in others.

Well, there's obviously the metaphor of going into the jungle is like making a movie, right?

Yeah.

This movie seemed like a huge pain in the ass. Did you ever go, "Why am I in this jungle?"

Yeah. Every day. The first two weeks I thought, This is all right. It's really uncomfortable. It was 100 degrees, 100% humidity. You say that to people and they laugh. But to be in that is really tough. You can't go in a T-shirt and shorts. You have to look like a beekeeper. You really have to cover yourself. Because mosquitoes, they have dengue and malaria. The boat captain got malaria and two people in the AD department got dengue, and that is no joke. So I had to cover myself up. So after about two weeks a kind of sameness to the routine set in.

Every day you'd wake up at 4:30 and put on your glasses and they were all steamed because of the humidity. I would take my rainwater shower, which was invariably freezing. I would get into my ridiculous outfit. I would get into a van that would take me to the banks of the river. It was pretty remote, where we were. You'd get into a raft and go either up the river or down the river for the shoot or you'd go into the jungle. It was kind of a good production plan in some ways. But every day for the same two weeks, a certain kind of madness or cabin fever sets in. You don't have telephones, you don't have Internet, you're dumping rainwater on your head. That sameness becomes enervating.

Did you feel closer to the characters?

Well, there was no way you can't. It's funny, towards the end of the shoot ... We kind of shot the jungle stuff in reverse. Which is to say we shot Fawcett as an old man with his son first because I wanted it to be this fountain of youth. So we removed his old man contacts and took away some of the aging make-up, to reinforce the idea that the jungle was where he wanted to be. And he didn't have to lose any weight. Then the second journey he lost some weight. Then by the end of the first journey was the end of the shoot and Charlie had lost something like 50 pounds, which is crazy. I remember Charlie and Rob on the raft and I was on the raft with them and in between shots I just saw Charlie having a death stare really, because he hadn't eaten and I just started rolling camera on him. It's in the movie. You can see this kind of expression. So you can't help but absorb what the experience.The movie went through two leading men before Charlie Hunnam, Brad Pitt and then Benedict Cumberbatch. Was the extreme physical aspect of the shoot a deterrent or was that unrelated?

What happened with Brad was he was all set to go on it and we started to talk and thought, well, maybe an Englishman should play this part. And then he went on to make "World War Z," ironically enough. Then the project lost momentum. But Brad was so great about it. I remember he called me and said, "Jimmy Jam, I'm going to stay on as a producer. I'm going to get this made." And I kind of went, "Yeah yeah."

I went on to make another movie, and when I was in post-production on that movie, which is called "The Immigrant," I got a phone call and they said, "We just made this movie called '12 Years a Slave' and we really like this actor Benedict Cumberbatch." I said "no," because I'm a loser and don't watch TV and "Sherlock" I didn't know about. I watch an old movie every single night, which is great fun, but TV I don't know. So I met with him and he had a strange, great-looking face, and I thought, This is interesting, I know what to do. So we put it together and the movie got financed and two weeks before we were scheduled to leave for Amazonia, I got a call from him and he told me his wife was pregnant and would give birth right in the middle of that Amazonia shoot. I can't very much force the position of "Who cares? Let your wife give birth in Amazonia." That's not a realistic position. So he had to back out. Then I totally gave up.

Then Plan B called again and said, "We're developing a script with an actor named Charlie Hunnam." And I said, "Absolutely not. I will not cast Charlie Hunman. Charlie Hunnam is wrong." My wife had been watching "Sons of Anarchy" and I said, "I will not cast an American." They said, "Well Charlie Hunnam is from Newcastle in England." I said, "He is?" So I had him over for dinner and he's the handsomest man in history and my wife falls in love with him. I thought he was funny and unbelievably smart and super dedicated and he committed himself to it in a crazy way.

Usually what happens in movies is the person that was supposed to be in it winds up being in it. And he really understood this lack of respect that I think he felt very deeply and I know that he felt that this movie was his shot at redemption of some kind. You feel it, which I thought really helped the movie. I really loved working with him. Perversely, given the physical brutality of it, in some ways it was a very happy shoot because I loved the people in the movie, we all got along great, but that was contrasted with the physical arduousness.

The book has these fantastic contemporary bookends with the author journeying into the jungle. Was that ever a part of the script?

Never. That's a great question you ask and it involves your approach to the adaptation process. I felt that that aspect of it where you utilize David Grann walking around going, "Well, where was Fawcett?" I felt that that approach, which is a kind of post-modern approach and had be done already and done brilliantly well, I didn't want to try. I could never top Spike Jonze's movie "Adaptation" so I didn't do that again, people would say he's following in Spike's footsteps. So you have to find your own way. I decided it was all about Fawcett. Because movies are not best suited for novel adaptations because it's too much story.

So if I immediately get rid of the David Grann stuff and immediately get rid of the James Lynch stuff which, if you've read the book, was quite helpful to me for the ending of this movie, I had something that was more like a novella, which was much more manageable. But even there I had to lose huge chunks of story which I loved -- the whole thing how he met and married his wife, it was like something out of a Bronte book, it's crazy -- and I had to reduce the eight trips to three, one for every act of the film.

But I didn't have a problem with that. It's always been a ludicrous criticism of narrative features like, "It's not totally historically accurate." This is not a documentary. You don't watch "Richard III" and start booing because it's not accurate. You use history as a very open way, as a way of expressing how you feel about the world, in this form, and so I figured I could just lose the Grann stuff. Now, if you've read the book you remember the James Lynch stuff, the investment banker in Brazil who brings his son, who talks about them making him kneel and the circle and all that. So I used that when thinking about what happened to Fawcett. I staged all the stuff at the end copying the James Lynch portion of the book and Lynch get saved basically by a seaplane coming down the river but Mr. Fawcett didn't have that option.

You could have just sent them down the river, since nobody really knows what happened. Why did you choose to dramatize it?

That's a great question. Why did I think that was the right thing to do? I guess I thought it was the right thing to do ... if I can verbalize it now ... I don't think of the story, despite his disappearing and despite his not finding this city he hoped for, I didn't think of the story as a tragedy. He has seen a part of the world and come to an understanding about it that no white Europeans back then even understand or understood. So there is a level of transcendence to his story and the mystery has lent him a kind of immortality. Now, it's not the same thing for his wife. In some respects it is a tragedy for her. That's why I felt the ending had to be on her being swallowed up by the same obsession. But it's different for her because she doesn't see that part of the world, it's been shut off to her because of her gender. I felt that was a very powerful idea. So in order to play with that idea I had to extend the ending as much as I could. Am I making any sense?

Is there ever any draw for you to do one of these giant studio things?

Yes and no. There is, actually. First of all, I don't know if they'd ever let me do one. But it would depend on how much freedom I had to express something that's interesting to me. It's sort of an open question. If I came in as a hired gun to just do traffic control, that's no interest. But if you can find a way to express yourself, it can be fantastic. I have huge admiration for so many directors. I kind of think it's the hardest thing in the world to make a movie. The difficulty level is insane. It's not like in the studio system, where those movies were consistently excellent in a way that movies aren't now.

But it was much easier for them. They had massive reshoots because actors were under contract and everything was on a stage so it was a controlled environment and the stakes were lower. Which is not to say John Ford isn't a talent, John Ford is God, but for most directors the machinery made it a little more accessible. But if I look at someone like Chris Nolan, who really personalized The Joker, he brought to it a kind of anarchy that is terrifying and it feels personal. That's great, if you can do that. I don't write the genre off at all. I've declaimed it because it's upsetting that it's the only movies being made at the studio. It's not that they suck. "Dark Knight's" conception of the Joker is amazing. But it's a problem when it's the only movies that are being made.

At a certain point, it becomes a situation where you start limiting the audience. I remember Detroit made a very concerted effort in the 1970s with the big four at the time. We're just in collusion that we're not going to make convertibles. The profit margins were small so they just didn't make them. No American automaker put out convertibles. The Japanese maintained the manufacturing of convertibles. Does this mean the Japanese automakers became great because they made convertibles? No. But it maintained a broad based interest in the brand and the product line.

If you only make one kind of movie, moviegoing is a habit and the studios used to make one to two prestige movies a year where they may have not made money, but they were there for the prestige aspect. And you had seven studios so you had 14 interesting films made and that was great. But the bean counters came in and now they're panicking. Because the only thing that's a hit is "The Avengers." But my attitude is, You created that environment. You made it. For 25 years you told audiences the only movie that mattered was Batman so what the f*ck do you expect? In economic terms, I argue it's a bad decision, even in a business model. I think I'm right.

I want to see a James Gray Batman movie.

I'd love to do that. That's an interesting character. But I don't think you can top what Nolan did.

"The Lost City of Z" opens everywhere this Friday. Come back next week for a look at the movie's haunting final shot.

The Lost City of Z