Heidi Ewing talks about her new film ‘I Carry You With Me’

In this interview with Moviefone, Ewing talks about making her first narrative feature, why her cast and crew was entirely Mexican, and the importance of holding on to your vision.

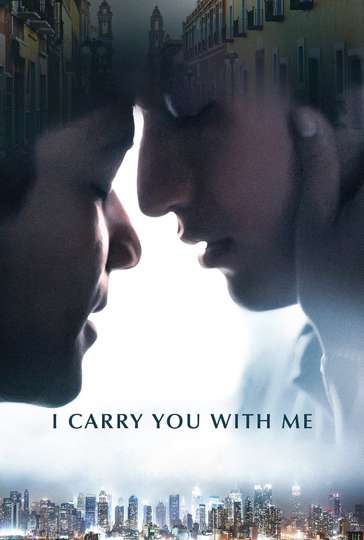

Left: Christian Vázquez & Armando Espitia in 'I Carry You With Me.' Right: Director Heidi Ewing (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics)

Director Heidi Ewing made her directorial debut co-directing ‘The Boys of Baraka’ with Rachel Grady in 2005. The two followed up that doc the next year with ‘Jesus Camp,’ which earned the pair an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Feature.

The pair has since directed seven more documentary features, including 2010’s ‘Freakonomics’ and ‘One of Us.’ At the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, Ewing made her solo narrative directorial debut with the romantic drama ‘I Carry You With Me.’ Inspired by the true story of her friends, Ewing’s film is an incredibly empathetic look at the human side of immigration.

Ewing spoke to Moviefone about the genesis of her film, the importance of telling these kinds of stories, and gives some advice for aspiring filmmakers.

Moviefone: You have said this was inspired by the story of your two friends - did you interview them before starting on your screenplay?

Heidi Ewing: I did a lot of interviews with them, with their mothers, with their brothers. I was also shooting cinéma vérité. All those scenes with the real guys are not scripted, they were just observational, cinéma vérité moments that I captured. So I filmed them over a long period of time while I was writing the script, before I was writing the script, because it was initially conceived as a documentary, and then I decided it would be better served by a narrative treatment. It was a ton of research, like going to Mexico and talking to the real drag queen that the character Cucusa is based on, getting what it was like to live in Puebla City as a gay man in 1994. It was a lot of research, but that was something that came natural to me as a documentary filmmaker.

MF: The editing is so seamless, like a memory, where it goes in and out, and you’re never really sure what year it is.

Ewing: My editor Enat Sidi is a genius. She’s edited all of my documentaries. She and I and the cinematographer developed this language, this cinematic language of memories that get triggered, and flash forwards and flashbacks. Like how your brain rushes through time into a specific moment and then spits you back out into the present day. We did a lot of trial and error in the edit to develop that language.

MF: In working with cinematographer Juan Pablo Ramírez, did you seek out someone who could really capture the feeling of both Mexico?

Ewing: The whole crew, the whole cast is Mexican. I was the only American on set. Cinematographer Juan Pablo Ramírez is incredible, you have not heard the last of him. I wanted to have solely Mexican talent working on the movie. He is just extremely versatile and a very tender-hearted person, and I think you can feel that in the shooting.

MF: The shots during magic hour and dawn are really stunning. Were there any specific lenses you used to capture that?

Ewing: We shot every magic hour. We made a deal that we would never miss a magic hour. Dawn in Mexico City at the time we were shooting was like seven minutes long. You could only get like one take before it was full sun. We actually shot that rooftop scene - when they have their first kiss - that is actually a sunrise. That was not shooting dusk for dawn. That was actually dawn. We got about one and a half takes and that’s what we got, so that’s what you see in the movie. We used Panchro/i Classic lenses from the 1960s with a lot of character in them. We also shot with Bausch-Lomb Baltar lenses, which are really hard to use. They take a tiny refraction of light, and they create this halo effect, so it’s hard to use those, but it was interesting. ‘The Birds’ was shot on Baltar lenses, and ‘Margot At The Wedding.’ They’re tricky lenses, but we used those as our back-up. We were looking for a nostalgic, but not corny, visual sense.

MF: Can you talk about how Alan Page Arriaga came on board as a writing collaborator?

Ewing: I was a couple of drafts in, and I realized I needed help and I wanted to have a Mexican voice help me write the movie even though I was basing it on my friends. I thought that was really important. So I asked around. My producers in Mexico City recommended Alan Page Arriaga, who was living in Mexico City at the time. We wrote the subsequent drafts remotely because he was in Mexico City, and I was in New York. Now he lives in Los Angeles, and he’s got a big writing career there. Together we crafted the movie. We would take turns, like I would write scenes that were Gerardo scenes, and he would write scenes that were Iván, and then we would switch. We really wanted the characters to be written in different voices, and it’s very hard to do that sometimes, to differentiate how people talk. So he became my good friend and writing partner on this movie.

MF: You spoke at Sundance about the difficulty in finding funding for the film. Why do you think there was so much resistance?

Ewing: I think it’s really hard to get funding for a foreign language film. Even though ‘Parasite’ won the Oscar and Americans have shown that they will read subtitles. ‘Minari’ is a great example as well. But you still have to go through the same rigmarole every time. Everyone asks you, “can you guarantee me it’ll be 50% or 60% in English?” and I’m like, “No. I can’t do that. These men speak Spanish.” That I think was the number one issue. But also it’s a gay subject matter, and it’s in Spanish, so you’ve got two areas that are considered “niche,” which I don’t think is the right way to look at it. That combination made it a little more daunting. But I will say that Black Bear Pictures and Sony Worldwide were crazy about the script, and I had full creative control on every aspect. In the end it worked out well, and I had really good partners.

MF: How do you think your work in documentary shaped your approach to narrative filmmaking?

Ewing: As a documentary filmmaker, I have an ear for how people really talk. Nobody ever finishes a sentence. People tend to interrupt each other. I can definitely hear bad dialogue and false dialogue because I spend my life listening to real people. That was helpful. I’m also partial to naturalism and the camera having to find the action, so we didn’t do a lot of blocking. I didn’t want the camera to be anticipating the action of the actors. So you’ll see in the cameras a searching and refocusing and looking for the action, and that was really happening. He was looking, we’re moving, we’re on the Easyrig, I don’t use tripods. We didn’t do a lot of static shooting or master shots, over the shoulder reserve. Like those traditional shots I would leave to the end. We were really trying to live moment to moment, intensely with each character. That is something I borrowed from my documentary work.

MF: How did you cast the younger version of your leads?

Ewing: I had a casting director in Mexico called Isabel Cortázar, and she knew what I was looking for. I wasn’t really looking for lookalikes of Iván and Gerardo. I found some guys who looked just like them, but they weren’t the right performers. I was looking for an essence of the real Iván because I knew he’d appear in the movie. Those soulful eyes, that deep nostalgia in the face. Also, paramount to the process was finding two actors who had actual chemistry together. So I cast Armando Espitia as Iván first, and then I went in search of his mate, his boyfriend, his partner. So I put Armando in the room with many different actors until we found Christian Vázquez for Gerardo. Christian and Armando just had a real natural, exciting chemistry together. So I cast based on that when it came to the two lovers.

MF: Did they meet with their real life counterparts?

Ewing: They wanted to talk to the real guys, but I asked them not to because I didn’t want them to be doing an imitation of the older version of the men they’re playing. Because they’re playing innocent, young men in their twenties in the throes of their very first relationship. I didn’t think that they could gain a lot from talking to a lived-in couple 25 years later. I asked them to refrain from doing that and stick with the script, and then when they came to New York to film the final scenes, they all met. They’ve become great friends. They’re very, very close. It’s a wonderful thing. It worked out for the best that they had a clean slate.

MF: Can you talk a bit about the importance of the dish Chiles en Nogada?

Ewing: Iván is really well known for his restaurants. He’s got two restaurants in Brooklyn. You can go to them in Williamsburg: Mesa Coyoacan and Zona Rosa. Chiles en Nogada is one of his signature dishes. It’s very hard to make. It takes days of marinating, and you’ve got to get the pears and the peaches and the pork. It’s a really complicated dish. It’s seasonal in Mexico, but he’s been able to find the ingredients year round, so he makes it year round. It’s just such a beautiful dish. The colors of the Mexican flag are in the dish because it was supposed to be a gift for the King of Spain who was visiting, so they wanted to invent a dish for him with the Mexican colors. It’s got a lot of historical resonance for Mexico, and it’s his signature dish. How he came upon the recipe in the film is a story Iván told me. When he told me that story, it was actually just before I left to start shooting in Mexico, so I added it to the script because I thought it was such a great story. So specific. You see the dish come up many times in the film because it represents his love of cooking and his homesickness for Mexico.

MF: What do you hope people take away from this film? What do you hope they’ll feel?

Ewing: I hope people feel uplifted by this story. It really is a love conquers all story. It’s a movie about the great sacrifice that people make for their families in order to create better lives for themselves and other people. I feel like the immigrant experience has become in so many ways a cliché and it’s a narrative that has been taken over by political figures, it’s become a partisan conversation. But this is just a human film, the human side of immigration. The accessible, real side of just people trying to do the best they can. People with ambitions and dreams and hopes. I feel like it’s a really emotional, touching ride, and hopefully it’s a different way we can talk about the immigrant experience than what we’ve been seeing in the last few years.

MF: Do you have any advice for women in the industry or who want to break in?

Ewing: I think you have to hold really tightly to your vision. If you have a vision for something, do not back down, do not let other people intimidate you and talk you out of your vision. The more specific your vision is, the more special the movie will be, and the more valuable you’ll be as a director. The moment you try to do it the way everyone else does it, or mimic a show that is popular, then your value, your currency as a creator goes down. It’s a long way of saying stick to your guns. You can push your vision though, but you have to have a strong stomach and be able to look people in the eye and defend that vision. Many people along the way, especially as a woman, will try to talk you out of what you know is best for your own film.

‘I Carry You With Me’ is in select theaters now.

I Carry You with Me (Te Llevo Conmigo)