Female Filmmakers in Focus: ‘In Balanchine’s Classroom’ Director Connie Hochman Talks About Making a Documentary About George Balanchine

This week, dancer-turned-director Connie Hochman talks about her debut documentary ‘In Balanchine's Classroom’ about choreographer and co-founder of the New York City Ballet George Balanchine. She also recommends Cindy Meehl’s heartfelt documentary ‘Buck.’

‘In Balanchine’s Classroom’ - directed by Connie Hochman

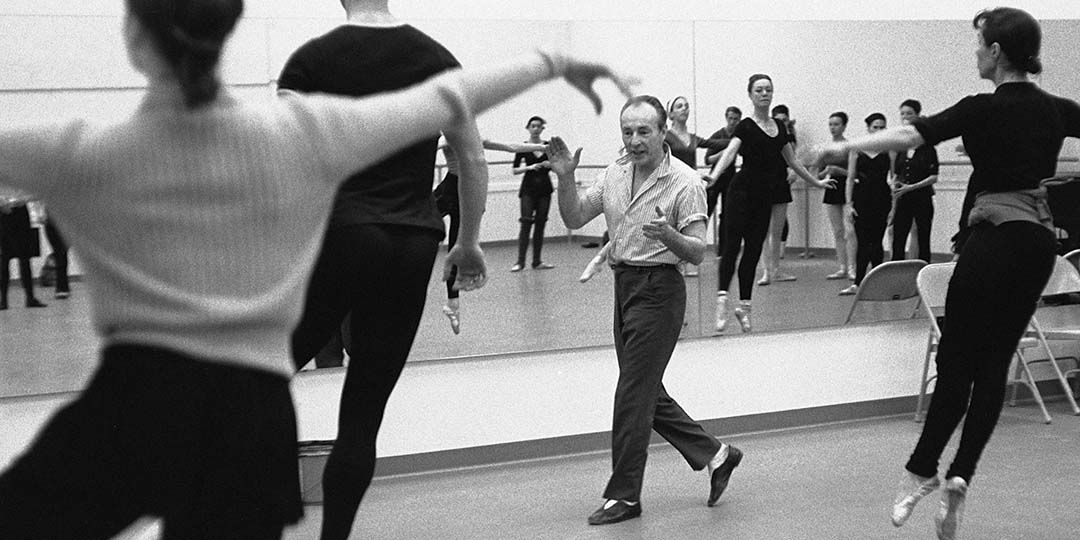

A scene from 'In Balanchine's Classroom,' directed by Connie Hochman

Connie Hochman trained at the School of American Ballet and danced alongside the New York City Ballet as a child in the 1960s. Later, she worked as a professional ballet dancer with Pennsylvania Ballet. In 2007, she began interviewing former Balanchine dancers, with the eye to writing a book about his impact on their lives. Eventually she realized the project ought to be a documentary. As she set out on this project, she consulted with documentarians like Louis Psihoyos (‘The Cove’), and Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine (‘Ballets Russes’). The film was completed with fiscal help from Dance Films Association and the Women Make Movies production assistant program.

Over the course of decades, Hochman conducted more than one hundred interviews with dancers and others who knew and worked with Balanchine over the span of his fifty years with the New York City Ballet and School of American Ballet. She also unearthed never-before-seen archival footage of Balanchine at work in America. The film also included extensive dance footage of Balanchine dancers who are working to keep his legacy alive within dance companies across the United States and Europe. Reminiscent of Wim Wenders’ 'Pina,' Hochman’s film is a lovely tribute to a trailblazing artist.

‘In Balanchine's Classroom’ is currently playing in select cinemas nationwide.

Hochman spoke to Moviefone about making the documentary.

Moviefone: What drew you to telling this side of George Balanchine’s story?

Connie Hochman: I was a professional dancer. I trained at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet from age 10 on. At that point, Balanchine was using a lot of the children from the School of American Ballet in productions with the company. Through my childhood and training, I got to be around Balanchine quite a bit. And of course, watched these amazing dancers, but also observed how he interacted with them. It left a very strong impression. I did not dance with the New York City Ballet. I danced with NYCB only as a child. I did not dance with the company as a professional. But I went on to dance with Pennsylvania Ballet. But it was a seed that was planted from those years. The more I danced and then later when I retired from dancing and became a ballet teacher, I just realized that there was something that I wanted to understand about Balanchine that I didn't get from just dancing his ballets. I knew from going through his school that he taught a morning class to his company members. This was something I wanted to find out about: why teach this class? They were already incredible dancers. They were dancers he chose from school when they were teens who were ready to perform. He chose these amazing dancers, but still Balanchine wanted to teach them every morning himself. I wanted to understand why.

MF: At what point did you decide it should be a documentary?

Hochman: When I decided I wanted to get their memories and their individual perspectives, before it was too late, I just started with a simple video camera because I thought that this was a book I'd like to start, and I thought to transcribe it would be easier if they were on camera, because they might actually show some things. I wanted to capture the way they express themselves so when I was transcribing I would not just get their voice, but I would get their gestures. There's a very wonderful book called “I Remember Balanchine” with memories of dancers, but it's more personal memories. What we had in mind was that this would be about his teaching. So after about five or so interviews, the dancers were so expressive and animated, and they were so different, one from the other, I thought this has to be visual. It is visual. It's hard to talk about movement and dance and music, but even just from the waist up, their gestures and expressions were captivating, and I thought it should be a documentary.

MF: There was a lot of footage from the 1970s. What was the archival process like?

Hochman: For a while I thought the documentary could almost be like ‘My Dinner With Andre,’ where individual dancers speak to each other because I thought it would be very interesting. But people who I was in consultation with said, no way, to not only do the talking heads. You have to find visuals. There's some film of footage of Balanchine that I knew about that had been in other documentaries. One person in particular who I spoke to, Andrea Meditch who is the executive producer of ‘Buck’ and ‘Man On Wire’ and a few other films, we had a few conversations, and she said I should search the four corners of the earth for footage of Balanchine if I was going to do this. She said I would find everything. She was sure there was more out there, and she knew nothing about Balanchine, she just knew from her experience that if I went really deep I would find something. And she was right.

I started reaching out to everyone in every corner I could. I was searching the Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, looking at their metadata. They have an incredible dance collection. I would sit there at like two in the morning, just reading the metadata to see if any footage mentioned Balanchine, even a few seconds of rehearsal where he stopped the ballet and actually got up and started talking to them about pointe work or how to walk on stage. I did find incredible footage that way. But the most amazing footage was actually taken by one of his dancers, even though the classroom was a private place. Balanchine did not let people watch class. He might let a special friend or a teacher watch rehearsal. He didn't mind at all. When he was choreographing, he was very relaxed, and he was focused. So people would watch him choreograph all the time, but the class was different. He was really pushing the dancers. They were trying things. He wanted them to feel unselfconscious, uninhibited. If they fell or if they looked awkward, he wanted that privacy for them. He wanted to respect the work process, so that was their private place. People were not allowed to watch.

But this one dancer in the company realized in the 70s that what was happening was incredible. Whether they're in New York or on tour or in Europe. She thought someone had to record this. Not just the performances, but also the day-to-day work. She adored his dancers. They were together all day, whether they're on tour traveling or New York. She knew them very well. It was a real family feeling. So this young dancer got a video camera in the 1970s, and he let her film. He would even wave to her sometimes. So when she wasn't dancing, she stood there and filmed and filmed and filmed. Some of the dancers who had done interviews and got a sense of how driven I was to do this film, started very discreetly telling me that someone had filmed, but they wouldn’t give me her name. Finally, someone gave me her name, so I started courting her. She was hesitant at first, but somehow I earned her trust and she gave all her footage. It was still on little cassettes. It wasn't digitized and was starting to deteriorate. That's why there are these little flickers of light and this beautiful graininess and sparkling, because it was deteriorating. We got it digitized in the nick of time. She gets credit, though I'm not giving her name away now because I want people to actually see the movie and see the footage. It was a miracle finding that footage of Balanchine.

MF: Do you think that working with him affected dancers for the rest of their lives?

Hochman: There's no question that it was transformative. One dancer actually said when you enter that room, he then entered that room with this energy, she says it was the beginning of your day and the beginning of your life. That’s how it felt; that every single day, it was totally unpredictable what would happen, and it was earth-shaking. For him, dance was a medium, and he was this master teacher. He was interested in individuals and developing them. He enjoyed people. He chose very strong personalities. He didn't care that much when he took them into the company how strong their technique was, because he knew he could develop their technique. He was interested in this spirit, this kind of fire in the belly.

As a young man in Europe, suffering from tuberculosis, Balanchine was left with one working lung before he came to America. I don’t know if it was because of that, but he was very soft-spoken, very gentle, very quiet. He had this awareness that life is short, and each day counts, and this is what impressed on them the most. Give it all now. Don't save anything. This is the chance. It’s like 'Hamilton,' and not giving away your shot. That feeling. This was instilled in them every moment of the day, from the class forward. The one time he stood back, totally hands off was when they were on stage. One of his dancers describes feeling like in performance they were in a bubble. Nothing could touch them -- it was their time -- and he, standing in the first wing, loved watching them dance. Then the next morning, he would know what he wanted to focus on. It sounds so cliché, as a way of life, his philosophy of life, but when they're actually expressing themselves, you know that he made them the people they became. Whether they teach now, or whatever they do, there's this urgency in all of them. I feel that every moment matters when I would be with them for an interview. They always would be there early. They would arrive 15-20 minutes early, ready to go.

MF: What do you hope people take away from the film when it's over?

Hochman: There are a lot of misconceptions about Balanchine. I would love for people to get a sense of what a positive force he was. This is for hundreds of dancers over generations. I mean, this is not a handful. I would also love people to get a sense of his dancers. I would describe it as courage, because I was a pretty good dancer, and I got strong, and I was pretty proficient, but I don't think I could have done that class. I just don't, it took a special kind of person to take that class. He was going to get to your potential. Whatever it took, he wasn't going to stop, So you had to have a lot of guts aside from your incredible talent. It probably won't ever happen that way. Other phenomenons will happen, but this particular artistic collaboration, this symbiosis, I don't think will ever happen again like this. It's very inspiring. It makes you question what you can bring to your own life, and what can you bring to other lives? It's very edifying. These are all just words I'm using, they're very empty. It's an experience when you absolutely can interface with it on the screen, it comes to life. I would like people to get to experience that with all their heart.

MF: Do you have a film directed by a woman that you think readers should seek out?

Hochman: That's a hard question for me because I didn't come from a film background at all. I was advised to watch as many films as I could. My husband, who is my partner in this, we would watch together and the more films I saw and the better they were, I found it almost intimidating in a way. Because I could never measure up as a director. I didn't have that background and experience and time either. I learned on the job and I surrounded myself with wonderful people, most of whom were women. I loved ‘Buck’, which was directed by Cindy Meehl. He was a teacher and was very intimate. The horse training, or people training depending on how you look at it, was really a medium again, like Balanchine. That film helped me a lot.

‘Buck’ - directed by Cindy Meehl

Director Cindy Meehl (center, with hat) working with her crew on 'Buck.'

Documentarian Cindy Meehl studied art at Marymount Manhattan College and The National Academy Museum and School of Fine Arts. She ran her own fashion labels before moving to a horse ranch in Redding, Connecticut with her in the 1990s. She met the famed horse trainer Buck Brannaman, who had been a consultant on Robert Redford’s 1998 drama ‘The Horse Whisperer,’ at a clinic in Pennsylvania where she had brought in one of her troubled horses. After that fateful meeting, she was determined to make a film about his work and life philosophies.

Filming of ‘Buck’ took place all over the United States including North Carolina, Washington, Wyoming, California, Montana, Texas, and even as far as France. Aside from tracing his day-to-day life, the film delved into his rough childhood and how Brannaman developed his philosophies. His aim is to teach people to communicate with their horses without punishment, but rather through leadership and sensitivity. ‘Buck’ premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Audience Award in the U.S. Documentary competition.

Buck