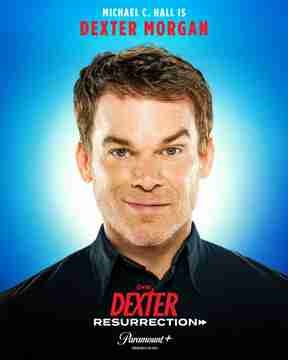

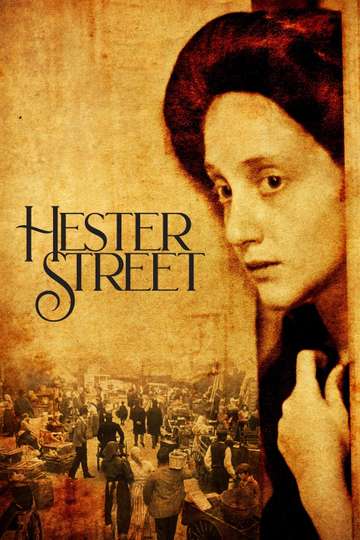

Marisa Silver, Daughter of Director Joan Micklin Silver, Discusses the 4k Restoration of ‘Hester Street’

Marisa Silver also talks about the impact and legacy of her mother’s work.

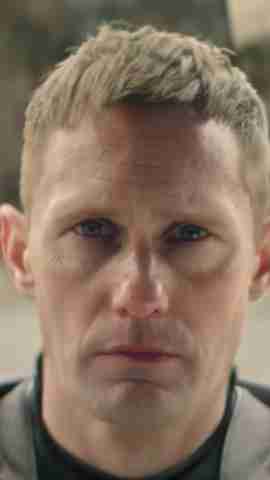

Carole Kane in Joan Micklin Silver's 'Hester Street.' Cohen Media Group is behind a 4k restoration of the movie.

Trailblazing filmmaker Joan Micklin Silver passed away last New Year’s Eve, leaving behind an indelible legacy of cinema. In recent years, Cohen Media Group acquired the rights to several of her films, releasing a critically-lauded restoration of her second film 'Between The Lines' in 2019. Her first film, 'Hester Street,' is the latest film to receive a restoration. When first released in 1975, the independently released take on immigrant Jews in 1890s New York City received widespread acclaim, and an Oscar nomination for its star Carol Kane. It was added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2011 for its cultural contribution to American cinema. Cohen Media Group’s new 4k restoration had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival and is now playing in theaters in New York City, Washington D.C., and Los Angeles.

Silver’s daughter Marisa Silver, a filmmaker and novelist, sat down with Moviefone at the New York Film Festival to discuss the new restoration and the impact of her mother’s films.

Moviefone: Can talk a bit about your mother’s career in general and why it was so trailblazing?

Marisa Silver: She made a series of independent films in the 1970s and the 80s. What was remarkable about her was, she was one of the first women directors who was able to do that. There were very few before her, and even during that time. The first feature film she made,'Hester Street,' was made on a shoestring budget, and was a success. For a lot of people at that time it was just an unusual thing for a woman to make a successful feature film. So I think that her work was both interesting on its own terms, you know, each film. But also, I think that she represented the beginning of a breakthrough, which is still ongoing, for women having the ability to get their due as film directors.

MF: Can talk a little bit about how this restoration came about, and how Cohen Media Group got involved?

MS: Cohen Media Group is interested in introducing to the public films that are important but may not be as well known. So they were very interested in presenting my mother's work. We thought it was a wonderful thing for them to take on her work and restore it and present it beautifully and to put it in the context of where that work existed in cinema history and to put my mother in a context. So we were delighted to have them do that. They've done an incredible job.

MF: Hester Street is based on an 1896 novella by Abraham Cahan. Do you know how your mother first came across this story and decided to adapt it for the screen?

MS: I have no idea how specifically she came across this story, although my mother's interest in her history and Jewish history in general was always ongoing in her life. I know that she read and searched out a lot of different stories and histories of Jewish life and Jewish immigrant life in America. Prior to making “Hester Street”, she made a short educational film about Polish immigrants. It was a subject that was sort of enduringly interesting to her, precisely because her family had immigrated to the United States. So I'm not sure how she fell upon the story in particular, but when she did, she became captivated by it. And I have not actually read the story, but I know that she changed the focus of it quite a bit, I don't think the story is focused on a female character to the extent that the movie “Hester Street” is. I think that my mother drew that story out from the original text and that became the focus of her film. Her interests were always in women and women seeking independence from structures that sought to repress them. So her way of reimagining the story on film was exactly that.

MF: Your mother often said in interviews her films were considered too ethnic. Can you talk a bit about that?

MS: 'Hester Street' was difficult in three ways. Not only was it about Jews, which was not a topic that people thought that audiences were interested in. It was also shot in black and white, which was a no-no because people assumed that contemporary audiences were not interested in anything that looked old-fashioned. And it was also mostly in Yiddish. So they created a challenge for themselves. I sort of admire them for doing it. The challenges were aplenty, but they stood firm. I think that one of the reasons they were able to stand firm was because they raised the money, and they distributed the film themselves, my parents, and they weren't really beholden to a studio or beholden to some person who was giving them all the money. I think that they were truly independent filmmakers in that sense. They probably would never have been able to make that film in any other condition. They raised the money themselves, they produced it themselves, and they distributed it themselves. So they kind of didn't have to confront the problem of who will make this film or who will distribute this film. They just did it themselves. Not easily, but they did it with a lot of tenacity and a lot of grit.

I remember as a little girl, when the film opened, and I remember going to the movie theater, and seeing the lines literally around the block. I remember the sense of astonishment that they had made this little shoestring budget film about immigrant Jews at the turn of the last century in black and white and Yiddish, and people came out to see it. I think it was such an incredible vindication for their vision.

MF: You are a filmmaker as well. How did growing up in a household with filmmakers inspire you?

MS: I'm sure 100%. I haven’t made films for a while now, and I don't do it anymore. I write novels now. But I'm sure that it was 100% inspiring. I had a mother who was out there doing something that she loved and something that was very personal and very expressionistic. I wasn't scientifically oriented, so I definitely had a creative bent, and seeing my mother do it, and seeing my parents do it without waiting for other people to give them permission to do it was, I'm sure incredibly impressive to me. It gave me a sense that with enough determination and grit and intelligence, I could manage to make that happen as well. The other thing about my parents was, when they realized that I had an interest in what they were doing, they included me in their process. Now looking back, I think, wow, that's kind of incredible. They used to have me be involved in casting sessions. I would get to read with actors. Everything was done in such a shoestring way. Once they brought me out to California when they were doing castings so I could help out. They had me help around the office and type up scripts and things like that. They were small little ways in which I was involved, but it made me feel empowered and important, and feel like it was a process that a human being could do. Because I saw them do it, and they let me be involved.

MF: How do you think audiences today will react to the character of Gitl and her strength?

MS: What I love about the character of Gitl was that she's very much a woman of her time seeking independence, right? So she's not a woman of today doing things that we would necessarily recognize. For instance, she wants to continue to wear her wig. And while some people may think that’s a sign of female oppression, to have to wear wigs, there are many women in the world who choose to do that. It can be seen as a form of male suppression, but she wants to. She doesn't want her child’s sidelocks to be cut off. Those traditions are important to her. I love the fact that it's not about a woman saying these traditions are terrible, and I don't want them. It's about a woman saying these traditions are important to me and I want to keep what's important to me. I think it’s an interesting and complex sort of feminism, right? Because you don't have to, you don't have to reject things that you love, and that are meaningful to your sense of identity, just because another person might think that they are somehow repressive. If they're not repressive to you, you claim them.

Gitl claims that things that are important to her, but she also rejects what isn't. What she really rejects is being abused. What she really rejects is being told how to think and what to think and how to be. So what she claims is her own identity. At the end of the movie, she's wearing her natural hair, but she's also marrying the Talmud scholar and making sure that the world they make themselves includes his abilities to keep studying because that's so important to her, and she respects it so much. It’s not a black and white, which I think is sort of marvelous. I think that was actually true of my mother's films in general. They're portraits of feminism and women claiming their power and their identity, but they're not black and white. They're shades of grey and a more nuanced understanding of what it means to claim your identity. It means to claim what's important to you, not with what another person might decide is or isn't important to the female identity.

MF: Gitl is one of my all-time favorite strong women characters in film. Her feminism isn't defined by what others want for her. It's defined by what she wants for herself.

MS: That one line in the film where she says, I don't want him back, and then she says, enough. That's it. It's so powerful. The interesting thing also about that role is she doesn't say that much. It’s a very quiet role. The transition that she makes is such small, delicate gestures. I think that was also very true of my mother's work. She sort of really loved the specificity of this small detail and what it can suggest.

MF: I remember watching Hester Street a few years back with my mom on Turner Classic Movies, and she wondered why she’d never heard it before. All I could say was, I guess some films fall through the cracks. I’m glad places like Cohen Media Group bring them back into the light.

MS: Most art falls through the cracks, right? Some of the art that survives the crack is not really interesting. A lot of it is, but some of it isn't. I think there's so much work that was valued in its time, but then time moves on. I don't think of her as being overlooked. I just think of her as having done her work in a certain time, and then time marches on. I think when you look at her work, it's really nuanced. It’s also funny. She's so funny. She was a funny person too. She had a wonderful sense of humor, and I think her humor comes across in all of her films. It's the combination of the seriousness of what she's trying to say about women and the humor and the foibles that she allows the characters to have, even as they search for their claim on their identities, is to me what marks the films.

MF: What do you think audiences will get from this film, watching it with fresh 2021 eyes?

MS: Immigration is something that is so front and center in our culture right now. What is the experience of the immigrant? Not so much, how do we deal with immigration. That kind of external view. But really, what is the experience as a person who has to change cultures, who has to figure out what assimilation means for them, who has to kind of carve out who they are in this culture? It's really challenging, in so many ways. I think that this film tells a story of that in a really wonderful way that is timeless.

The 4k restoration of ‘Hester Street’ is playing in select theaters.