David E. Kelley Has a Romantic Reason for Setting 'Goliath' in Santa Monica

Few people have had the kind of revolutionary impact on television -- and the legal drama genre in particular -- than Goliath."

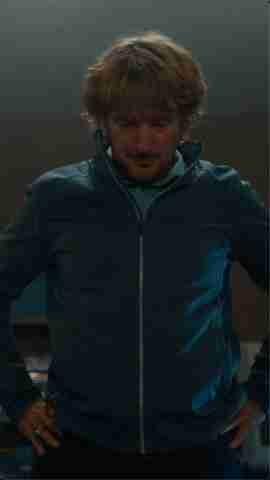

Since launching his Hollywood career, the one-time attorney has been at the center of some of the most genre-bending courtroom dramas of the past 30 years, including "L.A. Law," "Picket Fences," "The Practice," "Ally McBeal," and "Boston Legal." Now, he's bringing his trademark touches -- unique and often byzantine legal conundrums and quirky characters with complicated personal lives -- to Amazon Studios for his first streaming series, which focuses on Billy McBride (Billy Bob Thornton), a former hotshot attorney brought low by his own demons who finds himself the unlikely David figure facing down a mammoth corporate Goliath known for its deep pockets and penchant for down-and-dirty legal pummeling.

Ahead of the eight-episode series' debut today (Oct. 14th), Kelley joined Moviefone for a revealing conversation about reinventing and refreshing his own long-established approach to creating content, as well as the enduring appeal of TV series set in a court of law.

Moviefone: One of the things I really liked about "Goliath" was, along with the legal drama side of it, it was a little noir-ish, but set under the SoCal sun in Santa Monica. What was the fun of using that locale so specifically for this story? Places like the real-life bar and restaurant Chez Jay, your lead character Billy McBride's main hang, which I love.

David E. Kelley: Well, Chez Jay, it's kind of a small microcosm of the theme of the show. As Chez Jay exists now -- the whole area has been bought and developed around it, and it's hung in there, but it's this little, little fledgling, sort of decrepit, down-and-out establishment, with all this big stuff going on around them.

And I love Chez Jay, too. I met my wife [Michelle Pfeiffer] at Chez Jay. Our first date -- so you can see I'm a big spender. The idea: a little ocean lodge right next to it, I thought, man, if someone worked in that lodge, and Chez Jay was kind of his "office" and where he hung out, what kind of beast would that be? Started crafting the character, it just seemed particularly organic to Billy McBride.

And it's commensurate with the theme of the series: of this little, tiny spec of a gnat against this big behemoth, big data, big law firm. What chance does he have in today's world? So that's kind of where we started with it. It's a great vista. To look at Chez Jay, you kind of get old Santa Monica -- beautiful sun, but this squalor mixed in. It just captures a lot of the elements of the series.

I also thought that, while very contemporary, the show also felt a little like one of those great classic shows, like "The Rockford Files." It had kind of a flavor of that down-and-out guy that you're constantly rooting for, and he's finding his way. Was that in your head at all?

Not "The Rockford Files." I was probably inspired a little bit -- and so was Jonathan [Shapiro], the co-creator -- by "The Verdict," because we both loved that movie. Loved that sort of a little guy tilting at the windmills. But certainly separate -- distinctive of both "The Verdict" and maybe "The Rockford Files," our hero is not always a hero. There are going to be some episodes, I think, where you don't even like him. By the end of the eight hours, I think one of the verdicts, which will not be delivered by the jury in the case, but by our audience, is whether Billy McBride is more good than bad.

We wrote the character with love because we believe that flawed people are very human, and there are qualities about them to admire and love. But the math on him is 50/50. I think it's really going to be on the eye of the beholder. I think there'll be people in their living rooms taking issue [as to] whether they think he's more good than bad. That's certainly different from any protagonist that I've had in my shows. Historically, I've always kind of declared who the good guys are and who the bad guys are. This one, the audience I think will be the final arbiter.

William Hurt's character certainly introduces a monster, and I think that he stays true to a lot of his demonic qualities. But he's revealed to be a lot more human and fragile as we go on. So there may be some debate. I wouldn't be surprised, after some episodes, some people are feeling more compassion for Cooper than they are with McBride.

Given that you wanted to tackle this story of an underdog against a corporate giant, what did the process shake out of you as far as your feelings about that kind of conflict, and what you wanted to say about it?

Well, I have to say, the more we dug into it, the more demoralizing the truth, trying to be authentic -- and I won't give away the ending of the series, but it's kind of a "Rocky"-esque theme, where this guy who's barely a contender anymore is going up against this behemoth big law firm. And the idea that such a solo practitioner could win, the more we dug into the reality of it, the more and more remote and far-fetched it seemed. That was kind of demoralizing.

I'm a great lover of the law and the judicial system, and I want to believe that the justice has at least an even shot, as does truth. The more research we did, the more it became clear that this is a system that turns on resources, not truth. And we certainly mine that, but it's tough medicine.

Legal dramas have been the bedrock of television since practically the medium started. Why do you think they remain so popular, and why do you think creators like yourself are always able to find a new way into it to keep it fresh?

I would just be guessing as to why they remain popular with the public at large. I know what speaks to me, and I've always been fascinated with this machine, which is our legal or judicial system, as this imperfect and very flawed mechanism for legislating human behavior and morality.

It's the best thing we got. It doesn't work all the time, but it's the best thing that we got for righting wrongs, and sort of resetting or setting boundaries of morality. It's also winning and losing, so there's a competitive aspect to it. For me, it's still fascination with the law. It's also using the law as a device to explore characters has always worked for me and what I've enjoyed about the genre.

Where it's gotten more challenging, I think, is the filmmaking business of television has so grown, and the technological advances that have been made allow television shows now to do what only features could do in the past. As a result, traditional courtroom scenes can be very static, and not terribly filmic. So camera movement, some of that's challenging. As we go about crafting legal shows in the future, you've got to pay attention to how you tell your stories filmically to keep pace with the technological advances that have been made in the medium.

With all of your history with the traditional broadcast way of viewing things, what was the big surprise -- perhaps a refreshing element or something you didn't expect -- in doing a project with Amazon that was designed to be streamed?

We don't know the backend of it, the streaming, and what I supposed was the most daunting for me still is how we deliver our product to the audience. I'm kind of an old dinosaur: picks up the remote, tunes into a particular channel.

Amazon, as you know, you get a device or a subscription, and you align it with your hardware on the screen, and a television show will pop up. It's not as easy as Netflix, for example, where the Netflix icon is right up there and you scroll to it and hit select. It's getting easier and getting more user friendly. So the aspect of selling a show with Amazon is still unchartered territory, and I'm a little nervous about that.

But the creative process of being able to make the show was pretty great. Because, first of all, they said, "Just go. Make all eight episodes." So that allowed us to really tweak, and retool, and go back and fix things in [episodes] 1 and 2. We weren't putting all our eggs into that pilot basket without ability to adjust and fix. That was great.

I think, because we're not battling commercials, we can be more patient with our storytelling. When you have actors like William Hurt and Billy Bob Thornton, who are very, very subtle, and very, very nuanced, and sometimes slow in their delivery, but riveting, it's so great to be able to hold on them, and to watch them exercise their craft. When you've got six minute acts in broadcast television, I'm sure some of those scenes would have had to have been truncated and cut down. So there's a patience that came with this form that was fun.

You're one of the vanguard of adding serialization to traditional TV shows, and storylines that made the shows themselves feel bigger and a little more epic. So, in this case, how did telling a full story, essentially, in eight episodes -- knowing where you were going -- how did that affect the way you approached the material?

There was no real scientific difference in approach. It was probably more like writing chapters than it was episodes, because we knew where we were going. Certainly, we had to adjust and reconfigure along the way. We actually could have gone longer. We thought eight episodes would be plenty of time to tell the story we wanted to tell, and it was. We did. But we had a lot of scenes and ideas for avenues and directions that we were not able to mine, that we could have if we had more time.

One of the burdens of broadcast television is some of the storytelling is not the most efficient because you can't rely on your viewer to have seen prior episodes. So you've got to kind of bring them up to speed, contain a little exposition that is necessary to keep them afloat of plot development. Here now, you kind of operate under the assumption that the viewer is in for the whole thing, and they're watching every minute, and you don't have to take time out to bring them up to speed. As a result, I think you can probe a little deeper.