Female Filmmakers in Focus (TIFF Edition): ‘Violet’ Director Justine Bateman Discusses Her New Movie

The director also talks about working with Olivia Munn, and what inspired this story.

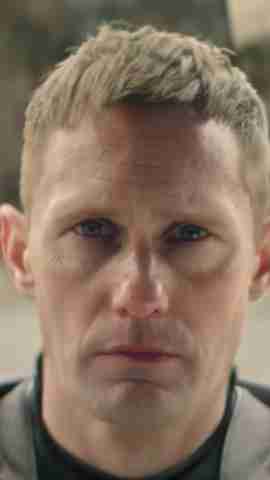

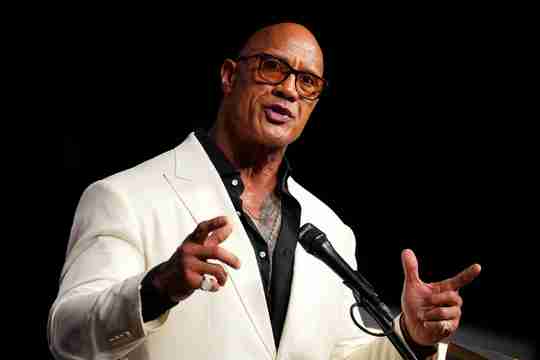

Director Justine Bateman and actor Olivia Munn on the set of 'Violet'

What if you confront that voice inside your head that always tells you that you’re not good enough? That’s the central conceit of ‘Violet’, starring Olivia Munn as a Los Angeles based film executive struggling to keep her internal insecurities at bay. Featuring a fierce performance from Munn, and set over just a few days, the film uses striking visual and aural cinematic techniques to embody Violet’s inner turmoil as she begins to find the courage to change her life drastically.

Writer-director Justine Bateman sat down with Moviefone after the film's special presentation at the Toronto International Film Festival to discuss its production.

Moviefone: What was the initial inspiration for this project?

Justine Bateman: Years ago, I made enough fear based decisions that at first I didn’t feel like I was me. I would see somebody who was really them, and I was like, oh my god I want that, and I thought I guess they were born that way. That’s not my lot in life. Then I realized I could get there, and I could cross that chasm, I was all in. It meant thinking about these critical thoughts objectively, as if somebody else is saying them. Would I give them as much validity if they were coming out of somebody else’s mouth? If I said to myself don’t wear that shirt to the party or no one will talk to you; saying it to myself, I’m giving it validity. But if I am imagining you were saying it to me instead, wouldn't I then question it? I wanted to put all these things in the film. For me, it’s a revenge film for me in a way. I feel like those fear based decisions or those critical thoughts stole time from me. So it’s my figuring out there’s other ways to cross that chasm, but I figured out a particular way to do it, and I’m going to take this recipe and tell everybody else how to do it. I wish I had seen this at nineteen because I would have gotten to that point earlier than I did.

MF: I think this is one of the best films I’ve seen about the need to sometimes cut off toxic family members. How did you develop that aspect?

Bateman: It’s one of those things in life that are sort of baked into our society. There are other things too, like for some pockets of our society it’s you must get married and have kids, and if you don’t, you’re breaking the rules. Even society - it’s all just an agreement. Stopping at red lights, or saying hello at the beginning of a phone call and goodbye at the end. Those are all just agreements that we have. It’s not that you must do them. You won’t combust if you don’t do them. That’s an example of one of those things. Like, I physically don’t have to go. Like, if I don’t go, what will happen? Will I get struck by lightning? What will happen exactly? Just to ask ourselves those questions is important. What I didn’t get into is that just because you’re related to somebody, doesn’t mean that you don’t have to behave as if you want to get invited back. How would you act with a friend? Family is not a license to just be an asshole to other people?

MF: I love the location of the John Sowden house on Franklin. How did you come to film in that location?

Bateman: I originally wanted to use this place that was being used as an office years ago that was also a Frank Lloyd Wright on Doheny, just below Sunset. It’s on a small street corner. But my location manager said it was in West Hollywood, so the permits and shooting would be difficult. But he said he had another Lloyd Wright for me to look at. When I saw it, it was perfect. I wanted Tom Gains (Dennis Boutsikaris) to be the type of person who doesn’t even like architecture or even understand it, but he wants to be in that building because he wants to be able to say to other people, “Come to my office. I’m in the Snowden house. You know, at the Lloyd Wright?” Because he knows that that is important to other people. He’s a sad character to me because he’s always trying to be part of things that other people find important so that he can be valued, because he doesn’t feel valued himself at all.

MF: Originally Dree Hemingway was attached, how did you eventually cast Olivia Munn? Did that casting change affect the character at all?

Bateman: Olivia was great, Dree would have been fantastic. Dree was originally cast, and I love Dree and hope to use her in something else, but I knew because of a few things I had to go in a different direction in that particular role. That was a phone call I hope to never have again. I think Dree Hemingway is incredibly underused and terrific, and I hope to use her again someday. Olivia was fantastic. There was a quality to her that I could see in her other projects that I really wanted to tease out and expand in this.

MF: When you mentioned how if the critical thoughts were said by someone else, you’d question them. Why did you have Violet’s internal monologue be a male voice?

Bateman: I wanted to make it very different from Olivia. Change the gender, change the tone. Even in the sound editing, we made it come from a different place physically in the theater than the other actors’ voices are coming from. What made a big difference for me was wondering: if these thoughts were coming from someone else, how would I think of them? So I wanted to give that to the viewer by dissociating this voice from her. If you think about it like it’s not you saying things to yourself, if you think about it as if it’s just pretend, it’s somebody saying it to you, it gives this objectivity that I wanted to give to the audience. That’s why the voice is so different. It’s not a comment on men. It’s nothing like that. I needed it to be as different from her as possibly, and part of that was changing the gender.

MF: I love the two different ways her anxiety is expressed on screen. How did you decide to show it her internal monologue and via the text on screen?

Bateman: One is the critical thought that she is having and the is like, “oh my god, oh my god, I’ve got to get out of this.” I know people have said there is so much going on, but that’s because yes there is. There is so much going on inside ourselves. We’re accustomed to doing this inside of ourselves, we do it in a split second, and we don’t even think about it. But if you were to split that all out and put it into a film, this is what it’s like, right? These critical thoughts are on us, but at the same time… like in the restaurant scene. The thoughts are saying “You can’t work with them,” but at the same time she’s saying to them inside herself, “Don’t leave, I want this. I want this.” That happens to us all the time, right? Where we’re saying something, but at the same time inside we’re like, “Why am I saying this right now?” Our brains are incredibly complex. It would be impossible to make a film that shows everything that is going on in our brains at the same time. We’re also having memories at the same time as we’re living in the present.

MF: I’d never seen the frenetic feeling of anxiety done quite like this on screen.

Bateman: Someone who feels anxious might relate to this film, but it’s really more about the human condition. It’s something that occurs for everyone. For some people, not as much as others, and some people are more in tune with it. It’s really just like the human condition to me.

MF: When we spoke 3 years ago, you were watching a lot of Michelangelo Antonioni on FilmStruck. Watching this, I felt like the interiority of the film was very similar to his films. Were his films an influence?

Bateman: When I first started going to films regularly, I was taken to films at the Nuart and there was a theater in Beverly Hills too, that would show double bills of old films all the time. My foundational film taste and influence is based in European films of the 60s and 70s. Godard, Fellini, Antonioni, Éric Rohmer, all of that. There are later films too, like Götz Spielmann’s ‘Revanche.' We referenced that film a lot in the collection of films my cinematographer and I were looking at. That stillness, that locked off shot in ‘Revanche’ is so outstanding. The way they come in and out of frame, is just like a whole other level. So when they were in the house I would want there to be that stillness, for the viewer, for Violet - so that’s why a lot of those shots are locked off. David Lowery employs a lot of that in ‘A Ghost Story’ also. I love how he does all that time folding in ‘A Ghost Story’.

MF: When the film is over, how do you hope people feel after they’ve gone through this experience with her?

Bateman: I hope they feel freer. I hope they went through it themselves and feel freer afterwards than they did before. If they weren’t aware they were having negative thoughts that were causing them to make fear-based decisions, I hope they come out of the theater going, “Oh my god, wait a minute. Those are lies?” Maybe someday doesn’t even imagine that those could be lies, and then to realize that and decide to see if they’re true. If those worse case scenarios are really going to happen. My hope is that everybody becomes freer after they see this film, and even if they don’t think it applies to them right now, maybe in a couple of years something will come up, and they’ll remember the ways that Violet got out of it, just as an experiment even. Just employ some of those and see if it works. If it doesn’t work, just go back to what you were doing. If it does work, hey!

MF: Can you recommend another film directed by a woman for readers to seek out?

Bateman: I think Lucrecia Martel is just beyond. There are some films where people go "X film is such a great example of.." this or that, and I’m like okay, but have you seen ‘La Ciénaga’ or have you seen ‘The Headless Woman?' These are much better representations of what you just said. I don’t know that people know her work, at least in this country, as well as they should. I think she’s fantastic. Also, I grew up watching Jane Campion films and Gillian Armstrong. I can’t tell you how many times I watched ‘Starstruck’ when I was like fifteen. They’re incredible filmmakers. I feel like the delineation is not between male and female, but it’s between good and not so good. That’s the dividing line that I feel like directors fall along. I love those filmmakers I just named not because they’re women, I could care less what gender they are. I thought ‘Shirley’ by Josephine Decker was so good. It killed me that it didn’t have the awards attention. One of the things I love about it was the ambiguity. She nailed it, the ambiguity is so true between those two women and how it kept shifting. That’s so hard to do. I know people like to be told who’s the good guy and who’s the bad guy, but life is not like that. Amy Seimetz is fantastic. That first year of ‘The Girlfriend Experience’ series? Like, get out! A fantastic actress and great director. You know who also is a great actress and director? Mélanie Laurent. ‘Breathe’ killed me. She’s a fantastic musician too. One of her songs is in ‘Violet’. You know, but, one of the best representations of female behavior and interactions I’ve seen is actually directed by a man. It’s a Spanish anthology film by Rodrigo García called ‘Things You Can Tell Just By Looking At Her' starring Holly Hunter. He captured so many tiny things about women. To me, it’s just about are you good or not.

'Violet' was part of the Special Presentation series at the Toronto International Film Festival this year.