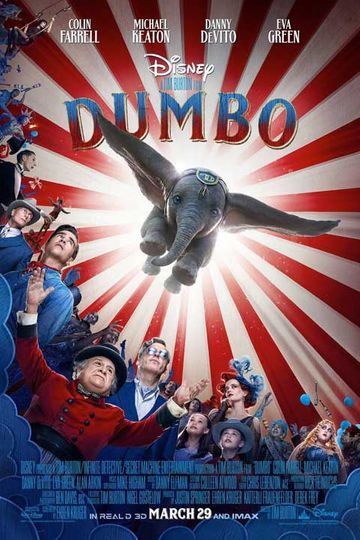

What It Was Like on the Set of ‘Dumbo,’ Tim Burton’s Latest Marvel

Disney’s original “Dumbo,” released in 1941, was a deliberate attempt at doing something lean, mean and emotionally resonant. It followed “Fantasia,” Walt’s wildly ambitious concert film, one that didn’t do what the studio had hoped on either a critical or commercial level. “Dumbo” was seen, in many ways, as a course correction; it was based on something inherently populist (a roll-a-book aimed at children) and clocked in at just over an hour (“Fantasia” had a runtime of a whopping 126 minutes). This was a movie that aimed to tug at your heartstrings, with messages that were simple and relatable. It was a far cry from the knotty intellectualism that tripped up “Fantasia.” And in some ways, Tim Burton’s new “Dumbo” can been seen as a similar attempt to recapture authenticity, after his earlier Disney live action remake “Alice in Wonderland” (a blockbuster, for sure, but one that was awash in computerized sets and imagery). Visiting the set of “Dumbo” back in 2017, it was easy to understand what the film would become because so much of it was physically there.

Burton’s “Dumbo” (out March 29th everywhere) takes its inspiration from the animated classic but doesn’t adhere much to the narrative. This movie is much bigger and more complicated, as everyone on set (from costume designer Colleen Atwood to production designer Rick Heinrichs, both longtime Burton collaborators) stressed how important it was for Burton to have actual sets, costumes, and props this time around. (“Alice in Wonderland” was groundbreaking in a number of ways, not least of which because of its status as a “virtual production,” wherein almost everything was created inside the computer.) The new film follows the small traveling Medici circus, run by Danny DeVito, as it is absorbed, following the arrival of Dumbo (a computer-generated character dreamed up by the geniuses at visual effects house MPC), by Dreamland, a corporate, stationary “destination circus” ruled over by Michael Keaton.

That meant that everyone had to work extra hard, creating custom, period-specific looks for not just a single circus, but several circuses, including Dreamland, a kind of proto-Disneyland whose stages were so large they were housed in a facility that used to build blimps for World War II. We were visiting some stages at Pinewood, outside of London, that were plenty huge, so you can imagine how immersive and complex those stages were.

Among the sets that we got to meander through were Valdevere’s apartment, which Heinrichs pointed out anachronistically embraced some art deco design (the movie is set in 1919), festooned with images of Eva Green’s trapeze artist (an element that isn’t lingered on in the final film); a trapeze area where Green’s character was practicing; and a large circus set that is integral to the final moments of the film so we will just keep mum about it besides to say that it was beautiful and enchanting and full of the kind of life and energy that Burton’s key collaborators kept reinforcing was integral to this project.

Atwood stressed how much more colorful the film was compared to some of Burton’s other, more monochromatic productions and said it was “very full of life, color, and joy.” She also stressed how important the original animated film was to this production, and touring the costumes, it was easy to see why, with nods to not only the circus and general atmosphere of the original movie, but specifics like the firefighter scene. (Producers Justin Springer and Derek Frey also promised a nod to the famous “pink elephants” sequence of the original in this new film. Hiccup.) Heinrichs promised a “storybook” feeling to the material, which is very promising given his background as a Disney animator, alongside Burton, in the early 1980s (a time when many of the fabled animators who worked on the original “Dumbo” were still at the studio).

And while Dumbo wasn’t there, for obvious reasons, there was tons of reference photos all over what we saw, to help everyone recognize what he would look like and just how central a role he would play. Springer and Frey teased that Burton had come up with a visual language that would make the audience feel like they were looking out through the pachyderm’s eyes. There was also a small stunt performer, who would act as a stand-in for eyelines for the actors. So even though Dumbo wasn’t really there, he was always represented.

Besides the movie’s missing star, though, it was staggering to see how little other visual effects work there would be; mostly set extensions and digital skies (inspired by Edward Hopper) courtesy of some very large green screens that were draped behind all of the sets we visited. But it was a far cry from the everything-but-Johnny-Depp-is-digitally-created ethos of “Alice in Wonderland,” in which actors wandered through a sea of green. Again, that worked and was a huge success, but it seems to have generally stressed out Burton to the point that his next animated-to-live-action-adaptation had to be done his way. Even the sawdust underneath the trapeze was real and very dusty. Heinrichs says that the stages were decided on early on: “Being on stage allows you to focus more, and to light expressively and focus the audience’s attention much more specifically.”

And what he brings up is a very good point, in regards to being able to draw out of an audience a very specific emotional response, which seems both easy (Dumbo is so cute) and incredibly difficult (especially as we’re expected to invest in an all new family, led by Colin Farrell, whose story runs parallel to the main narrative). We got the sense from everyone on set that they were taking this project very seriously even though, as he rushed in between set-ups, Burton joked that he didn’t know if he was making a comedy or a drama. Maybe, just maybe, he’s making a new classic.