No Twists, Only Discoveries: What Makes 'The Village' Shyamalan's Most Underrated Movie

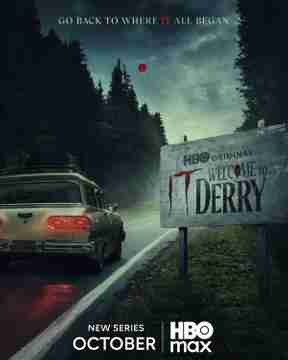

After more than 20 years and almost a billion and a half dollars at the box office, the only twists and turns more surprising than ones at the end of an M. Night Shyamalan movie are those in the filmmaker’s career. His breakthrough films “The Sixth Sense” and “Unbreakable” earned him instant prestige and impossible-to-meet accolades but just a few years later he was branded a hack and a has-been. After mounting a comeback and bankrolling his own films, Shyamalan rekindled mainstream interest in his work, although even this has led to further unexpected ups and downs.

All of this is to say, Shyamalan has endured his share of hits and misses, certainly commercially, but critically as well. He is a polarizing figure, and his work is sharply divisive. But just as his most beloved films are perhaps not as impeccable as once believed, neither are his failures as ineffective or flat-out bad as critics have claimed. “The Village,” at the time reduced to another mystery with a maudlin third-act twist following too closely in the footsteps of his previous work, remains perhaps his most under-appreciated work, which with the benefit of 15 years’ distance, can be properly seen as a remarkable meditation on grief, fear, and ultimately, hope in the face of generational trauma.

Starring Joaquin Phoenix, Adrien Brody and a then virtually-unknown Bryce Dallas Howard, the film explores a remote and mysterious 19th-century Pennsylvania community called Covington where resident live in constant fear of nameless monsters that live in the surrounding woods. Lucius Hunt (Phoenix), poised to become a leader for the village’s next generation, develops a curiosity about the larger world after asking for permission to visit nearby communities for medical supplies. But when Lucius is critically injured by Noah (Brody), a developmentally-disabled young man jealous of his burgeoning relationship with Chief Elder Edward Walker’s (William Hurt) blind daughter Ivy (Howard), the young woman is permitted to venture into the woods to seek medicine and first aid. She is only allowed to go on her journey after learning the village’s real secret: the monsters are the Elders themselves, dressed up in costumes and meant to protect themselves and the residents from real external dangers.

Shyamalan tips his hat to audiences early in the film with this news -- much of the movie’s advertising was built around the notion of “Those We Don’t Speak Of,” so it felt at the time like he was uncovering his trademark “twist” early in order to subvert expectations, and/or to get them out of the way. But what that choice does is deepen the mystery around the village (why exactly are the Elders so protective of their community, or perhaps, fearful of the outside world?) that eventually drives the emotionality of what started as a suspenseful monster movie. Ivy’s vulnerability alone in the woods would have been unbearable to watch (especially after her two sighted guides abandon her) but her choice to forge ahead alone gives her agency and dimensionality, especially after she encounters, well, a few things that she cannot explain.

The first is another person who’s not a part of her village. Since she is blind, she does not realize that she’s arrived at a guard tower that protects their village from the modern world, and the staff there is initially as surprised to see her emerge from the woods as she is to arrive in their presence. This, somewhat unfairly, was pegged as Shyamalan’s second “twist .“ After deceiving and dazzling audiences in his earlier films, the thought was that he was trying to top himself, or at least maintain his reputation for pulling the rug from beneath them. But I never considered the information that everything is taking place Right Now to be altogether surprising; though the Elders adhere strictly to a code and lifestyle of a bygone era, they do not seem like actual people of a bygone era. As a result, this information, parceled out at the right time, further deepens our curiosity about what is going on back in Ivy’s community and why it is so insulated from the world.

The second surprise Ivy encounters is, apparently, one of those creatures that her father had earlier told her did not exist is hot on her trail. We later learn that Noah, the disabled boy who nurses a crush on her, discovered one of the monster costumes, put it on, and followed Ivy into the woods. Despite her terror, she tricks him into falling into a deep hole where he dies. She does not know it’s him. But the momentary existence of something we were told is a fabrication upends the viewer’s orientation, and complicates our willingness to believe the elders.

The guard tower unearths most of the important information that is germane to the “plot” -- Covington exists in a no-fly zone, a community built and designed to shield its members, and their descendants, from the grief of their normal lives. But this is only brought full circle when we witness the Elders open their “black boxes,” which contain mementos of their past lives, and in particular, signifiers of the losses they create the village in order to escape. Particularly in a more immediate post-9/11 landscape, this sort of isolation and self-protection may have seemed a little too on the nose; but in subsequent years, that notion feels surprising prescient, at least in terms of the intellectual and emotional silos constructed by many in the years since to protect themselves from unwanted ideas, beliefs or thoughts.

But Ivy’s return to the village, triumphant and whole, conjures as much a sense of reassurance as it does a provocative question: how will the Elders maintain control upon this insular community now that she has found others outside of it? This is a world whose mythology is coming apart, and it takes only a skeptical young follower to start pulling at its fraying edges. But they are untarnished by the trauma of their parents and guardians, and Ivy is proof that they can survive even the immediate dangers of the creatures that haunt the woods around the village. “The Village” resonates most strongly because it shows how one generation can endure unimaginable pain, and how the next can help heal it. This is what makes the movie’s real revelations thematic and not narrative. The revelations serve not as a twist, but a discovery.