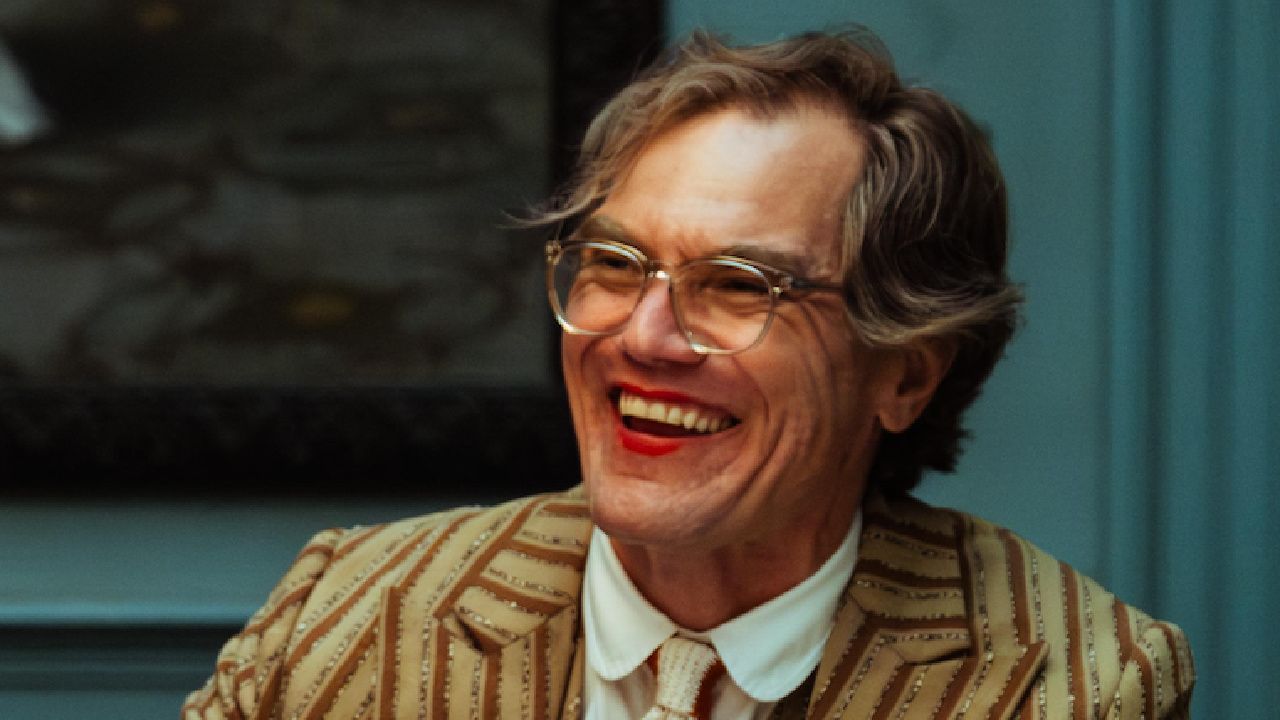

'Star Trek' Writer David Gerrold's Tribbles Remain Popular 50 Years After Their Population Explosion

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of "Star Trek," which first aired on Sept. 8, 1966 and has continued to boldly go forward as one of the most enduring, influential and visionary television creations of all time, Moviefone is offering a week-long look at five decades of the futuristic franchise.

In 1966, David Gerrold was a 22-year-old fledgling writer who caught the debut broadcast of a then-brand new science fiction television series called "Star Trek." Within a year, he was not only a writer working on the show, he had created one of the soon-to-be iconic series' most unusual -- and whimsical -- alien life forms. And today, 50 years later, "The Trouble With Tribbles" remains a hallmark of the original series' episodes.

Gerrold would enjoy a long and fruitful association with Star Trek: The Animated Series," including the follow-up episode "More Tribbles, More Troubles"; the unrealized 70s-era sequel series "Phase II," which paved the way for the later theatrical films; and the earliest days of "Star Trek: The Next Generation," as well as penning both fiction and nonfiction books on the subject of "Star Trek."

Gerrold's television work stayed largely rooted in genre -- he created the Sleestaks of "Land of the Lost" and penned episodes of sci-fi series like "Babylon 5" -- and he had an acclaimed and prolific career as a science fiction novelist, most notably with his semi-autobiographical Hugo and Nebula award-winning novelette "The Martian Child," which became a full novel and then the 2007 film of the same name.

Over the course of Gerrold's career, "Star Trek" fans have multiplied almost as rapidly as Tribbles and the writer has seen the phenomenon only increase in scope and influence over the course of five decades. With much of his work on the franchise now collected with the newly released "Star Trek 50th Anniversary TV and Movie Collection" -- featuring all three seasons of the original '60s series, the six theatrical films starring the original cast and, for the first time in HD, every episode of the animated series -- Gerrold shared his remembrances of getting in on the ground floor of one of the most celebrated and enduring properties in television and film history.

Moviefone: You've certainly have enjoyed a long and fruitful association with the "Star Trek" franchise, and you started as one of the earliest fans. I'd love to hear about the first time you watched "Star Trek," and the effect that it had on you.

David Gerrold: It was September of 1966 -- God, I can't believe it's been that long ago! -- and we saw this network advertising a new series, and I saw one commercial for "Star Trek." I thought, "What the hell is that?" I was a big science fiction fan, and here comes this spaceship that doesn't look like anything we've ever seen before. And I thought, "Well, that is the stupidest looking spaceship I've ever seen," right?

It was 8:30 on Thursday night, so I tuned in, and the episode was "The Man Trap" by George Clayton Johnson. And I was watching it, I was like, "Beamed down? They don't land? That's kind of dumb. It violates the laws of physics." They had this guy with pointed ears who has no emotions, and I think, "Well, that's not going to be a really interesting character ..." I'm sitting there being very skeptical.

They arrive on the planet, and the scientist is investigating some kind of alien pyramid. And I look at the set direction, the set design, and the doorway to the alien pyramid is not human proportion. Somebody on that how was trying very hard to create an alien environment -- a believable alien environment!

The story as it happened was not bad, because a little bit later on when the salt vampire creature is walking down the hall, and here comes Uhura, the salt vampire creature shows up as a very handsome black man for her. And I realized that was very clever. Because it shows the creature showing up as desirable.

So that was when I started to get hooked, and I thought, "Well, I don't want them to screw it up, and I know science fiction, and I know script format, so I'm going to submit an outline." I submitted an outline, Gene L. Coon [the showrunner] was very impressed with it, and invited me to submit outlines to the show, and I submitted "A Fuzzy Thing Happened to Me," and they bought it.

Were you aware of what a Cinderella story that was at the time? Or did you think, "Oh, this is just how showbiz works"?

I was very conscientious about structuring the story so that it would play as a story. I didn't realize how funny it was until after the story was very carefully outlined, and Gene L. Coon said, "Put this piece back in. It's the funniest piece in the show." That was the scene between Kirk and Scotty asking about who started the fight. I began to realize there's a lot of humor in it that I'm just going to see where it goes.

I was very pleased that it turned out even funnier than I thought it would be, because I wanted to be quietly whimsical, and it turned out to be laugh out loud funny, which was even better. I was even happier, because I always wanted to be good at comedy.

The night it was aired, a friend of mine was raving about how good he thought it was. And I turned to him and I said, "It's only one episode of one TV show. In 20 years, who's going to remember it?" It's 50 years later. The universe must have said, "Challenge accepted, David."

Where did the first notion of Tribbles come to you, and did they emerge fully formed as we see them in the series?

Well, I wanted to do rabbits in Australia [which historically bred at an uncontrolled pace], and I realized that we can't do live creatures because of all kinds of just technical concerns, and concerns for the animals. So I thought, "What can we do to represent these creatures?" My girlfriend at the time, Holly Sherman, had a keychain with fluffy, black ball on it, and I thought, "That's it! We use black balls."

I described them as black balls, and the prop man, Wah Chang, who's worked on a lot of big movies, hired a lady -- I forget her name -- and she showed us about 500 or 600 Tribbles, and we used those in the show. We just had a great time with them. They photographed beautifully.

Another one of your big contributions is Captain Kirk's middle name, Tiberius. I'm very curious where that inspiration came from.

I'm a big fan of Roman history, so I had just been reading a book about how the ancient Romans were experts in torture, and Tiberius was just a monster. Dorothy Fontana and I were on a panel at a "Star Trek" convention in New York, and one of the fans asked, "What does the T stand for?" Without thinking, I said "Tiberius." That got a big laugh.

And then a year later, we were doing the animated series, and just for the hell of it, I had somebody address him as Captain James Tiberius Kirk. Dorothy got on the phone and checked with Gene Roddenberry. He said, "That's fine with me -- go ahead!" I don't think he was paying too much attention. He was like, "Tiberius -- okay, great." So it got put into that animated episode, and from that moment on he's been James Tiberius Kirk.

Gene Roddenberry was a complicated man. Tell me a little bit about your relationship with him throughout the many years you were involved in "Star Trek."

Well, I admired Gene a lot. He was a great visionary, and he was absolutely a charismatic public speaker. That was a strength of his: that he could inspire people, and when he talked story and said, "I want you to write the story that you can't write anywhere else," that was very exciting. You wanted to write the best story you were capable of. You wanted to write a better story than you were capable of.

The problem is that Gene had a -- I don't know how to phrase it tactfully: he had a dark side. I think he was insecure around other people with talent and ability. I'm not certain. So he wasn't very good at sharing the fame. He'd speak to an audience, he'd talk about what he created, and he rarely acknowledged what anybody else had contributed to the show.

When I came aboard "Star Trek: The Next Generation," at the beginning it was very inspiring, because we had this blank slate, we had this blank canvas to fill. But when his lawyer appointed himself chief of staff for the entire series, and took advantage of Gene's failing health and brought aboard a bunch of producers who did not know "Star Trek," and didn't want to listen to Dorothy or myself -- we did know "Star Trek" -- it became a very unpleasant situation where office politics got out of control.

And Gene was no longer quite the master of his own show. We were never quite sure what was true from one day to the next. So it was very unfortunate, and when I left the show ... this was the one flaw in his character that I found most difficult: Gene always had someone else to blame. No matter what went wrong, he didn't manage it well. It was always, "It's NBC's fault," "Paramount's fault," "It was Harlan Ellison's fault," "It was the studio's fault." When I left the show, Gene blamed me for a while, and that hurt a lot because I had only wanted to just do the very best "Star Trek" for Gene. So I felt a little bit betrayed.

Now, after I got past that, I realized he'd done me a favor because I wouldn't have adopted the most marvelous little boy and became a dad, and got to write some of the best novels of my career. Thinking back on it, I think I learned a lot from Gene. A lot about how to be good, and a lot about what not to do. Despite any issues I might have had with Gene, he gave us "Star Trek," and I think that mitigates a lot, because he was passionate about "Star Trek." And if it hadn't been for him, we'd have never had the show.

So we have this incredibly iconic thing that is going to change our culture for generations to come, because it's about the possibilities of the future, it's about a future where we're all thriving and doing well and all have opportunities and we're all included. So it's a very positive view of the future, and I give Gene enormous credit for that, because I don't think anybody else has been able to create that kind of a vision of a future that works for all of us with no one and nothing left out.

So despite any issues I might have had with Gene at the time, I have to acknowledge that he did something remarkable and extraordinary.

One of the other unsung heroes of "Star Trek" is Gene Coon, and I'd love to hear more of your memories of him in particular. He's a little bit of a mystery man to the public at large as far as his great contributions to "Star Trek."

I admired Gene L. Coon as a consummate producer. He understood you had to have a good script, you had to have the right actors for it, and you had to have it be about something. And he understood that Tribbles could be that way, but he also understood that with every other script that passed under his desk, under his management, under his responsibility, whatever.

He understood that it was that every episode had to have a specific sparkle to it, whether it's a comedy or a drama, or a tragedy, he understood that there needed to be this magic, or a statement that had to be really pertinent. So operating from that context, he encouraged writers, and he listened well to writers, and he listened to ideas, and if the ideas worked, he said, "Yeah, that's it. Let's do that."

He was a charming man, but, pardon the expression, he was also a no-bullshit man. He was focused on getting the job done. So if you were in a conversation with him, there wasn't a lot of chitchat. It was, "Let's solve this challenge ahead of us. Let's tackle this challenge and see what we can do that's clever, and exciting, and interesting." I cannot say enough good things about him.

I mean, I won't say he was flawless. He smoked those God awful cigars that killed him. But in terms of, if I had to pick one producer who I would love to work with again, and again, and again, he would be way up there near the top of the shortlist. Probably the top. He respected writers.

We know that there is definitely more "Star Trek" in the future with "Star Trek: Discovery," the new show headed up by Bryan Fuller. You want to sit down with the producers and see if there's a story you can pitch them?

Well, they're doing a story arc across 10 episodes, so everything has to be integrated into their story arc. So I think that they have a writers' room. I know Bryan Fuller and Nick Meyer -- they're just spectacularly good writers. They're very optimistic that they're going to come up with something very exciting. I look forward to seeing what they're going to do. So far, my phone hasn't rung, but if it did, I'd be there in a heartbeat!

Here we are at the 50-year mark in this franchise that was a huge part of your life for a very long time. What does it mean to you to see everything that it's become: a phenomenon; a way of life, in many respects? It's a singular, beyond-a-television-show kind of experience. Tell me what that means to you.

Well, it's like being one of the Beatles, only without being mobbed everywhere you go. It's that you get to see that something you did, something you created, has had this enormous impact on the audience, and that's probably one of the luckiest experiences a writer can have, is to see that the audience has responded so enthusiastically. It lets you know you weren't wasting your time.

I find it sometimes overwhelming, sometimes embarrassing because ... I'm speechless sometimes. I'm amazing at the enthusiasm of the audience. That they have connected so strongly, and I'm humbled by it. It was my first show, and all of a sudden here I am part of something so iconic that it has changed the world.